One of the great advantages of viewing the Christian faith from a Jewish perspective is the door it opens for looking at things from a different angle—for asking questions one would otherwise never ask. For some time I have been asking questions about the Lord’s Table, as well as the ritual of baptism performed in the traditional Christian church. The questions I’ve been asking myself relate to the origin of these two institutions, as well as their biblical foundations. I would like to share with you my quest as it relates to the Lord’s Table. I hope to be able to stimulate your thinking and perhaps together we can move further in pursuit of the truth.

Questions about the Lord’s Table always arise around Pesach (Passover), and for good reason. The very texts (both in the Gospels and in 1 Cor.) which are read by Messianic as we celebrate the Passover season are those which the Christian church reads before the Lord’s Table. For Torah observant believers, these texts give deep meaning to the yearly festival, but to the Christian church, these texts describe a ceremony which has almost no resemblance to a Pesach seder. So the first question, and perhaps the most important one, is simply this: how did the Lord’s Table get started? Where can we find its origin?

But finding the origins of an institution like the Lord’s Table is far from easy. The only sources we have are the Apostolic writings of the scripture, and the few works left to us by the early church fathers. Furthermore, in the writings of the church fathers, it is often impossible to discern what is genuinely from their hand, and what has been added by later generations of the church. But a reading of these historical, early church documents leaves me with a grave misgiving. All specific dates aside for the moment, it is absolutely clear that by the 2nd century the church had universally accepted the view that the Lord’s Table imparted salvation, that only the bishop had the authority to administer the Table, and that there were great Mysteries attached to the Table which were fit only for fully accepted members of the church, not for those newly joined to the religious community.

What is more, it becomes clear when reading the church fathers that there was every attempt to fashion the Table as something distinct from

Jewish rituals. This fits with the increasing emphasis upon the superiority of Christianity over Judaism, and makes one suspicious about why the Table was initiated in the first place, and how it gained such a central place in the worship of the early, Gentile church.

For someone who already has questions about the Lord’s Table, to discover that very early in the history of the ordinance the leaders of the church had invested it with such heresy causes new questions to arise. Could something initiated by Messiah, carried on by the apostles, be so entirely changed so quickly? These and other questions are what have prompted me to engage in this study.

My procedure is simple: I want first to investigate what the church fathers of the first four centuries of the common era had to say about the Lord’s Table, and then turn my attention to the primary portions of Scripture which the Christian church has used to support her view of the ritual. One word about the perspective I have as I begin this study: I do not want to presuppose anything (though I readily admit my inability to be fully objective). That is to say, I do not want to begin with the premise that Yeshua initiated what we now know as the Lord’s Table, nor do I want to rule out such a thing. I want to look at the history of the ordinance in the early years of church history, and exegete the texts of scripture associated with the Lord’s Table, and then make conclusions. So, the fact that I am unwilling at the beginning to say that Yeshua and His apostles initiated the Lord’s Table is not to deny that they did. It is only to say that I want to wait for clear evidence to support my final conclusions.

Finally, as I read the church fathers in search of what they taught on the matter, I will be collating their comments and will have these available in a separate handout for those who are interested. In this article and the parts that will follow in subsequent issues of Chadashot, I will only be giving a few examples. But I want to read the primary sources (in their English translations) for myself and not rely upon the word of others. Giving you the references and/or the excerpts will allow you to do the same thing.

Church History and the Lord’s Table

The first four centuries of the common era produced a church which had entirely divorced herself from her Jewish roots. As such, the Lord’s Table had become a ritual invested with meaning impossible to derive from the Pesach seder from which it supposedly arose. So central was the Lord’s Table (or Eucharist, as it was usually called by the fathers) to the 2nd-4th century church that the rules and theology which surrounded it essentially molded the church in her entirety. For example,

the Incarnation was viewed from the vantage point of the abiding presence of Yeshua at the Table. The means by which God grants salvation to sinners was understood as requiring the Table. And, the Table defined the roles and status of church leadership. Since the bread and wine, through the invocation of thanksgiving, actually became the body and blood of Messiah, and since He had overcome death for all time, anyone eating the Eucharist was assured resurrection and eternal life. How could the body and blood of Messiah, which, by eating, became one with the body of the worshiper, ever undergo eternal damnation? With such emphasis upon the salvific aspects of the Table, it became necessary to guard who administered the Table, and to whom it was offered. Strict rules were laid down regarding the absolute need of a duly ordained Bishop to be present at the offering of the Table. Who could actually eat the bread and drink the wine was also closely regulated. From this stage, the ability of the church leader to impart eternal life was only a step away, and full sacerdotalism was inevitable. The Table was viewed as the altar, the bishop as high priest, and thus, the Roman Mass was established.

In general, the Lord’s Table as it is portrayed in the writings of the 2nd-4th century church fathers may be summed up under the following headings:

The Lord’s Table was viewed as a sacrifice requiring a Priest (Bishop) to preside.

Justin Martyr (2nd century), in his teaching against the Jews (Dialogue with Trypho the Jew), states that the sacrifices of the Jews are replaced with a much superior sacrifice, namely, the Eucharist. He interprets Mal 1:11 as prophesying that the Gentiles would offer sacrifices and writes:

[So] He then speaks of those Gentiles, namely us, who in every place offer sacrifices to Him, i.e., the bread of the Eucharist, and also the cup of the Eucharist, affirming both that we glorify His name, and that you profane [it]. [Anti-Nicene Fathers (hereafter ANF), Vol. 1, p. 424-5]

Ireneaus teaches that the Table is a sacrifice (oblation):

Those who have become acquainted with the secondary (i.e., under Christ) constitutions of the apostles, are aware that the Lord instituted a new oblation in the new covenant, according to [the declaration of] Malachi the prophet. . . . For we make an oblation to God of the bread and the cup of blessing, giving Him thanks in that He has commanded the earth to bring forth these fruits for our nourishment. And then, when we have perfected the oblation, we invoke the Holy Spirit, that He may exhibit this sacrifice, both the bread the body of Christ, and the cup the blood of Christ, in order that the receivers of these antitypes may obtain remission of sins and life eternal. [ ANF, Vol. 1, p. 1190]

Ignatius, a 2nd century church leader, teaches the same:

Take ye heed, then, to have but one Eucharist. For there is one flesh of our Lord Jesus Christ, and one cup to [show forth] the unity of His blood; one altar; as there is one bishop, along with the presbytery and deacons, my fellow-servants: that so, whatsoever ye do, ye may do it according to [the will of] God. [ANF, Vol. 1, p. 164]

Even a very early document (end of the 1st century), such as the Epistle of Clement to the Corinthians (sent from Rome), suggests that the Bishops and Deacons may function in parallel with the Priests and Levites of the “Old Testament,” an apparent allusion to their function of serving the Lord’s Table (cf. 1Clement 42:4-5).

In like manner, the Didache (14:1–3) makes direct reference to the Eucharist as a sacrifice, making the whole notion very early. The Didache was a document written for the instruction of new converts to Christianity, and is dated by most scholars around 90–120 CE (though some would date it earlier).

The Lord’s Table conveys to those who partook of it the remission of sins and assurance of the resurrection

Ireneaus (2nd-3rd Century):

And then, when we have perfected the oblation, we invoke the Holy Spirit, that He may exhibit this sacrifice, both the bread the body of Christ, and the cup the blood of Christ, in order that the receivers of these antitypes may obtain remission of sins and life eternal.

The Apostolic Constitutions 2nd-3rd Century: (speaking of the Bishops who the people are to reverence):

who have fed you with the word as with milk, who have nourished you with doctrine, who have confirmed you by their admonitions, who have imparted to you the saving body and precious blood of Christ, who have loosed you from your sins, who have made you partakers of the holy and sacred eucharist, who have admitted you to be partakers and fellow-heirs of the promise of God! [from Bk 8, Sec. 4, p. 844 [ANF, Vol. 7)]

The Vision of Paul (apocryphal work), 2nd-3rd Century:

Therefore the great Paul straightway taking her hand, went into the house of Philotheus, and baptised her in the name of the Father and of the Son and the Holy Ghost. Then taking bread also he gave her the eucharist saying, Let this be to thee for a remission of sins and for a renewing of thy soul.

Transformation of the Bread & Wine into the Actual Flesh and Blood of Yeshua

The Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, or the belief that the bread and juice of the Lord’s Table actually become the flesh and blood of Yeshua, is well established in our time. But the seeds of this doctrine are found in the early church fathers, as the following excerpts will show:

340-397 St. Ambrose

Speaking of those who refuse to accept the doctrine of transubstantiation he writes:

In what density of ignorance, in what utter sloth must they hitherto have lain, not to have learnt from hearing, nor understood from reading, that which in God’s Church is so constantly in men’s mouths, that even the tongues of infants do not keep silence upon the truth of Christ’s Body and Blood at the rite of Holy Communion? For in that mystic distribution of spiritual nourishment, that which is given and taken is of such a kind that receiving the virtue of the celestial food we pass into the flesh of Him, Who became our flesh. [Series 2, Vol. 12, p. 141]

(318-386) Cyril, Bishop of Jerusalem

Writing about the use of oil to impart spiritual benefit to a person, Cyril makes an analogy to the Lord’s Table:

But beware of supposing this to be plain ointment. For as the Bread of the Eucharist, after the invocation of the Holy Ghost, is mere bread no longer, but the Body of Christ, so also this holy ointment is no more simple ointment, nor (so tosay) common, after invocation, but it is Christ’s gift of grace, and, by the advent of the Holy Ghost, is made fit to impart His Divine Nature. Which ointment is symbolically applied to thy forehead and thy other senses; and while thy body is anointed with the visible ointment, thy soul is sanctified by the Holy and life-giving Spirit. [Series 2, Vol. 7, p. 354]

Cyril’s teaching, based upon the teaching of even earlier fathers, made this logical assertion: if, when taking the bread and juice, a person actually imbibed the very flesh and blood of Yeshua, and if His flesh and blood is indestructible, then the person who takes “the Eucharist” is assured resurrection unto eternal life. How could someone who, in his own flesh carried the body and blood of Christ, perish eternally in hell? Note the following:

We beseech the merciful God to send forth His Holy Spirit upon the gifts lying before Him, that He may make the bread the body of Christ, and the wine the blood of Christ, for certainly whatsoever the Holy Ghost has touched, is sanctified and changed (ἁγίασται καὶ μεταβέγληται). [Series 2, vol. 7, p. 69]

(331-395) Gregory, Bishop of Nyssa

In his famous catechism, Gregory writes concerning the Eucharist:

The Eucharist unites the body, as Baptism the soul, to God. Our bodies, having received poison, need an Antidote; and only by eating and drinking can it enter. One Body, the receptacle of Deity, is this Antidote, thus received. But how can it enter whole into each one of the Faithful? This needs an illustration. Water gives its own body to a skin-bottle. So nourishment (bread and wine) by becoming flesh and blood gives bulk to the human frame: the nourishment is the body. Just as in the case of other men, our Savior’s nourishment (bread and wine) was His Body; but these, nourishment and Body, were in Him changed into the Body of God by the Word indwelling. So now repeatedly the bread and wine, sanctified by the Word (the sacred Benediction), is at the same time changed into the Body of that Word; and this Flesh is disseminated amongst all the Faithful. [Series 2, Vol. 5, p. 915]

(296-373) Athanasius

And we are deified not by partaking of the body of some man, but by receiving the Body of the Word Himself. [Letter 61, in Second series, vol. 4, p. 1375]

A charge was laid against a certain Macarius that he willfully broke the cup that was used for the Lord’s Table. Athanasius defends him in one of his writings. Within this defense Athanasius gives a description of such a cup:

This is the only description that can be given of this kind of cup; there is none other; this you legally give to the people to drink; this you have received according to the canon of the Church ; this belongs only to those who preside over the Catholic Church. For to you only it appertains to administer the Blood of Christ, and to none besides. [Second series, vol. 4, p. 419]

(393-458) Theodoret

In describing heretics against which he wrote, Theodoret says:

They do not admit Eucharists and oblations, because they do not confess the Eucharist to be flesh of our Savior Jesus Christ which suffered for our sins and which of His goodness the Father raised. [Second series, Vol 3, p. 486]

Augustine

Augustine speaks of the “communion of the blood and body of Christ” [Series 1, vol. 1, p. 579], a phrase that might in our ears have no special meaning, but in his time was quite significant, for the simple reason that the term “communion” was taken quite literally, i.e., that the actual blood and body of the Messiah comes to be one with the worshiper so that the worshiper is assured eternal life.

Apocalyptic Work: The Vision of Paul

In an anonymous, apocalyptic work entitled the Vision of Paul, written most likely around 388 CE, heretics are described by the following:

And the angel answered and said unto me: If any man shall have been put into this well of the abyss and it shall have been sealed over him, no remembrance of him shall ever be made in the sight of the Father and His Son and the holy angels. And I said: Who are these, Sir, who are put into this well? And he said to me: They are whoever shall not confess that Christ has come in the flesh and that the Virgin Mary brought him forth, and whoever says that the bread and cup of the Eucharist of blessing are not this body and blood of Christ. [ANF, vol. 10, p. 243]

Acts of the Holy Apostle Thomas (Apocryphal, 4th century)

After casting a demon out of a woman, Thomas administers the Eucharist:

And the apostle standing by it, said: Jesus Christ, Son of God, who hast deemed us worthy to communicate of the Eucharist of Thy sacred body and honorable blood, behold, we are emboldened by the thanksgiving and invocation of Thy sacred name . . . And having thus said, he made the sign of the cross upon the bread, and broke it, and began to distribute it. And first he gave it to the woman, saying: This shall be to thee for remission of sins, and the ransom of everlasting transgressions. And after her, he gave also to all the others who had received the seal.

Ireneaus

Speaking on the incarnation of Messiah, and the phrase in Eph 5:30 (Textus Receptus) that “we are members of His body, of His flesh and of His bones,” he writes:

And as we are His members, we are also nourished by means of the creation (and He Himself grants the creation to us, for He causes His sun to rise, and sends rain when He wills). He has acknowledged the cup (which is a part of the creation) as His own blood, from which He bedews our blood; and the bread (also a part of the creation) He has established as His own body, from which He gives increase to our bodies. . . . He does not speak these words of some spiritual and invisible man, for a spirit has not bones nor flesh; but [he refers to] that dispensation [by which the Lord became] an actual man, consisting of flesh, and nerves, and bones, ó that [flesh] which is nourished by the cup which is His blood, and receives increase from the bread which is His body. And just as a cutting from the vine planted in the ground fructifies in its season, or as a corn of wheat falling into the earth and becoming decomposed, rises with manifold increase by the Spirit of God, who contains all things, and then, through the wisdom of God, serves for the use of men, and having received the Word of God, becomes the Eucharist, which is the body and blood of Christ; so also our bodies, being nourished by it, and deposited in the earth, and suffering decomposition there, shall rise at their appointed time, the Word of God granting them resurrection to the glory of God, [ANF, vol. 1, p. 1089-90]

5. Then, again, how can they say that the flesh, which is nourished with the body of the Lord and with His blood, goes to corruption, and does not partake of life? Let them, therefore, either alter their opinion, or cease from offering the things just mentioned. But our opinion is in accordance with the Eucharist, and the Eucharist in turn establishes our opinion. For we offer to Him His own, announcing consistently the fellowship and union of the flesh and Spirit. For as the bread, which is produced from the earth, when it receives the invocation of God, is no longer common bread, but the Eucharist, consisting of two realities, earthly and heavenly; so also our bodies, when they receive the Eucharist, are no longer corruptible, having the hope of the resurrection to eternity. [ANF, Vol. 1, p. 1003]

And this food is called among us ευχαριστία [the Eucharist], of which no one is allowed to partake but the man who believes that the things which we teach are true, and who has been washed with the washing that is for the remission of sins, and unto regeneration, and who is so living as Christ has enjoined. For not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Savior, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh. [ANF, Vol. 1, p. 354 (ch. 66, Dialogue with Trypho)]

Ignatius (Epistle to the Smyreaens) [2nd Century]

In identifying heretics, Ignatius points to their unwillingness to admit that the bread and wine of the Eucharist actually become the body and blood of Messiah. He also teaches that taking the eucharist assures resurrection:

They abstain from the Eucharist and from prayer, because they confess not the Eucharist to be the flesh of our Savior Jesus Christ, which suffered for our sins, and which the Father, of His goodness, raised up again. Those, therefore, who speak against this gift of God, incur death in the midst of their disputes. But it were better for them to treat it with respect, that they also might rise again. [ANF, Vol. 1, p. 180]

Observations

This brief summary of some of the church fathers confirms the fact that the Lord’s Table was very early practiced as a ritual that would have never met with the approval of Yeshua or His apostles. The magical or mysterious character attached to the Table in the changing of bread to flesh and blood to wine fits more with the pagan rituals of the day than with any teaching of Messiah. Furthermore, the idea that salvation comes through taking the Eucharist is clearly contrary to the Scriptures, and especially to Paul’s epistles in which he regularly taught that salvation was by faith alone apart from works. What is more, teaching that the Lord’s Table is the means of salvation would require that a complete change in how God saves a sinner occurred after the death of Messiah.

The anti-Jewish flavor that surrounds comments of the fathers about the Lord’s Table also makes one very suspicious about its origins. Were the early church fathers seeking for a way to mimic the sacrificial system of the Tanakh without having to accept the Jewish reality attached to it?

Having studied what the early church fathers have to say about the Lord’s Table, I have found nothing to support the idea that the Lord’s Table, at least as it is taught by the fathers, could have been initiated either by Yeshua or His Apostles.

“Breaking Bread”

The phrase itself in the Greek utilizes the verb κλάω (klaō) or its noun form κλῆσις (klasis) plus the common word for bread, ἄρτος (artos). The verb κλάω (klaō) and related words have the basic meaning “to break, divide” but is found in the Apostolic Writings only in reference to bread. What would the corresponding Hebrew/Aramaic have been for the phrase “break bread”? The phrase occurs only three times in the Tanakh, at Isa 58:7, Jer. 16:7, and Lam 4:4. in the Lxx, the same Greek term used throughout the Apostolic Writings. In Is. 58:7, however, the Hebrew verb paras is translated by a different Greek word, διάθρυπτw (diathruptō, not found in the Apostolic Writings).

Jastrow, in his Dictionary of the Talmuds and Midrashim, notes that the

verb paras can be used alone without adding the word “bread” to mean “a piece of bread” or “half a loaf,” and became a term for the minimum maintenance given a member of the household, much like our English “room and board” where “board” stands for the food one eats.

The question that faces us first is whether or not this phrase, “to break bread,” was a common phrase in the 1st century for “eating a meal” or whether it was a technical phrase reserved for the observance of the Lord’s Table. Bauer, Arndt, and Gingrich in their Greek Lexicon make the statement that the phrase was used to describe when “the father of the household gave the signal to begin the meal” and they go on to state that “this was the practice of Jesus.” A quick check in Liddell and Scott, Greek-English Lexicon, which deals with classical Greek sources, yields not one reference to the phrase “breaking bread” except those found in the Apostolic Writings. From this one may surmise that the phrase was of Semitic origin, not Greek, and thus its appearance in the Apostolic Writings may be traced to the Jewish community out of which the Apostolic writings arose.

If the phrase was a common Hebrew idiom for “eating a meal,” we would expect to find evidence in the extant literature, and we do. For instance, b.Berchot 46a:

“When the time came to start [the meal], he said to R. Zira, “Will the master begin for us [by breaking bread]?” He said to him, “Does the master not concur with the statement of R. Yohanan, who said, ‘The master of the household is the one who breaks bread’?”

This is only one example of many to be found in the Bavli. Throughout Berchot, the phrase “break bread” refers to the opening of the meal at which time the berachah (blessing) is said. Thus, the phrase “break bread” is not quite equivalent with “eating a meal” but came to mean this since the meal could not be served until the initial blessings were said. As such, “to break bread” came to mean “to begin the meal.”

Most scholars agree with this conclusion. Note as an example the remarks of Behm:

The technical use of “to break bread” or “breaking bread” for the common meals of primitive Christianity is to be construed as the description of a common meal in terms of the opening action, the breaking of bread. Hence the phrase is used for the ordinary table fellowship of members of the first community each day in their homes.

With this in mind, we may now review the occurrences of the phrase in the Apostolic Writings, found in Matt 26:26, Mk 14:22, Lk 22:19; 24:30, 35; Acts 2:42, 46; 20:7; 27:35 to see if the context suggests that the meal is common or if it describes a religious ceremony, i.e., the Lord’s Table.

The first three references listed above are the parallel accounts of the final Pesach that Yeshua shared with His disciples. The breaking of bread in the Pesach seder is well known by all and needs no further explanation.

Luke 24 is the account of Yeshua’s travel to Emmaus with two of His disciples. The text explains that “their eyes were prevented from recognizing Him” (v. 16) until they ate together. It was at this point that their eyes were opened: “ . . . He took the bread and blessed it, and breaking it, He began giving it to them. And their eyes were opened . . . .” This is clearly describing a common meal, not the Lord’s Table. But why did they recognize Yeshua at this point? Was it because the master was obligated to begin the meal with the berachah and the breaking of bread and when Yeshua took the role of Master they saw Him in a different light? Did they see His hands at this point and recognize the scarring? Whatever the case, it was in the context of the opening blessings at the meal that their eyes were opened (cf. v 35).

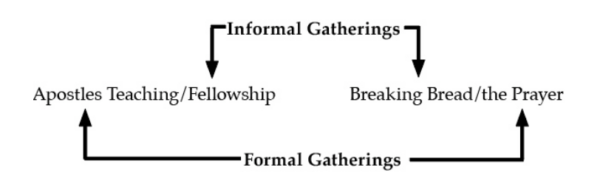

Acts 2:42, 46 describe the early Jewish followers of Yeshua as they fellowshipped in community in Jerusalem. Verse 42 details 4 items that characterized the community’s life: apostolic teaching, fellowship, breaking of bread, and prayer. It should be noted that “prayer” is plural and preceded by the article in the Greek text, so “the prayers” most likely refer to the synagogue or Temple liturgy. With this in mind, it is possible to see a chiasm in these 4 terms: “teaching,” the primary function of the synagogue, is paralleled by “the prayers,” describing the core of Jewish liturgy. “Fellowship” (Greek koinania) and “breaking of bread” thus describe the community aspects of the group.

Why would they be grouped this way? To emphasize that the community aspects (fellowship, i.e., owning things in common, and breaking bread, i.e., eating together) were held together by study on one side and worship (prayer) on the other. Once again, however, the phrase “breaking of bread” does not mean taking the Lord’s Table, but rather the sharing of common meals, as v. 46 plainly states: “And day by day continuing with one mind in the Temple, and breaking bread from house to house, they were taking their meals together with gladness and sincerity of heart.”

Acts 27:35 simply describes Paul’s attempts to urge the people to eat aboard the ship on which they were traveling. Facing a raging storm and the real possibility of shipwreck, the passengers had not eaten for 14 days. In an attempt to get them to eat, Paul “took bread and gave thanks to God in the presence of all; and he broke it and began to eat.” Once again the phrase simply describes a common meal.

The one reference using the phrase “to break bread” to which many pointed as referring to the Lord’s Table is Acts 20:7 — “And on the first day of the week, when we were gathered together to break bread, Paul began talking to them, intending to depart the next day, and he prolonged his message until midnight.” What exactly is this gathering? Why were they meeting on the first day of the week for a meal? Was this a special meeting just to take the Lord’s Table?

When exactly did this meeting take place? While it could have been Sunday night, the context would favor Saturday night, i.e., the beginning of the first day as reckoned by the Jews. Thus, after spending the Shabbat together in the Temple and/or synagogue, it apparently became the custom of the early Messianic Jews to eat a meal together following Havdalah (the conclusion of Shabbat), a meal in which the Gentile believers also participated. This meal became known as the Agape (Jude 12) or Love-meal, a meal in which the unity of Jew and Gentile in Yeshua was celebrated as an illustration of God’s love.

That Acts 20:7-11 is describing this Agape meal seems likely because the text emphasizes the presence of lamps. This proves not only that it was nighttime, but also aligns with the custom of the 1st century to light a lamp for the Havdalah ceremony. In the 3rd century Christian work The Apostolic Constitutions, a complete halachah is set forth for the church on exactly how the Agape was to be conducted, including instructions for lighting the lamp. Why was a lamp lit for the Agape meal? The best explanation is that it originally was connected with the Havdalah ceremony of the Messianic congregations.

Having looked briefly at the phrase “break bread” and noted each occurrence in the Apostolic Writings, what is the conclusion? First, the phrase “break bread” is a Jewish idiom for beginning a meal, and was not a common phrase among the Greeks. Its use by the later church therefore reminds us of the original Jewishness of the early church. Secondly, each time the phrase is found in the Apostolic Writings, it describes the initiation of a meal and not a congregational ceremony like the Lord’s Table or Eucharist. To equate “breaking bread” with the Lord’s Table is to impose a liturgical ceremony upon a phrase that simply describes the initiation of a meal. If we are to find the origins of the Lord’s Table in the Scriptures, it will have to be elsewhere than in those texts that utilize the phrase “to break bread.”

In the 3rd part of this series, I will be looking specifically at the text of 1 Cor 10 and 11, and the phrases “Lord’s Table” / “Lord’s Supper.” Perhaps here we will find the origins of this long practiced ritual.

The Lord’s Table

Having looked at the manner in which the “Lord’s Table” was practiced and taught during the early era of the Christian Church, as well as at the phrase “break bread,” we must now turn our attention to the specific texts that have been the basis for the current practice. In this installment, I want to look at the first important text, namely, 1 Cor 10:21, “You cannot drink the cup of the Lord and the cup of demons; you cannot partake of the table of the Lord and the table of demons.” In studying this and subsequent texts, my purpose is to examine the (1) terminology used, (2) the larger contexts of the passages and then to (3) draw a conclusion as to the meaning and application.

The phrase “Lord’s Table” or “Table of the Lord” struck me as curious when I began to ask basic questions about the origins of the ceremony often described by that name. Why is it called the “Lord’s Table”? Did such a phrase already exist in Hebrew custom, and if so, what did it mean? What is the “Table of demons” which is put at odds with the Lord’s Table by Paul in 1 Cor 10?

My first inquiry was into the Mishnah. I remembered the well-known saying in Avot 3:3, “Rabbi Shimon says: ‘If three people ate together at a table without speaking words of Torah, it is as if they had eaten of sacrifices offered to the dead [idols], as it is said: ‘all their tables are full of filth without room’ [Is. 28:8]. But if three ate at a table and spoke words of Torah, it is as though they had eaten from the table of God, [מִשׁוּלְחָן שֶׁל מָקוֹם, literally “from the table of The Place”] as it is said: ‘He said to me this is the table which is in the presence of God’ [Ezek 41:22]. Here, the Sages consider the study of Torah to transform an ordinary table into the “Lord’s Table,” parallel to the altar of the third Temple (which is made of wood). Now this is very interesting since the earliest reference we have to a table connected with the divine presence is, of course, the table in the Tabernacle, Ex 25:30, “And you shall set the bread of the Presence [לֶחֶם פָּנִים] on the table before Me at all times.” The Lord’s Table, from a Hebrew perspective, is thus clearly connected with the Tabernacle/Temple service.

This idea of the Lord’s Table being connected with sacrifice is indicated in another way in this well-known saying of Avot. If people eat at a table and do not engage in discussion of the Torah, according to the Sages it is equivalent to having eaten sacrifices offered to idols. In other words, from the viewpoint of the Sages, a table substitutes for an altar, and the sacrifices upon it are either for idols or for HaShem.

In 1 Cor 10, Paul makes a very bold statement: “you cannot partake of the table of the Lord and the table of demons.” The average Christian, when reading this, defines the “table of the Lord” as the eucharistic ceremony or the communion service. It’s easy to read this and picture the table draped in cloth at the front of most Protestant communion services. But what then is the “table of demons?” Did the pagans have a similar ceremony?

The context gives us the answer. Paul is talking about sacrifices—sacrifices offered to demons (pagan gods) as contrasted by those offered to God in the Temple. Note the context: Israel of old provoked God at Sinai with their idolatry (v. 7), which included immorality (v. 8) as well as lack of faith (vv. 9-10). In other words, they participated in sacrificing to idols. Paul encourages his readers to see the difference between pagan and holy sacrifices, because the Temple sacrifices were witnesses to the salvific work of Messiah, especially the Pesach sacrifice. Messianic Jews were still going to the Temple and participating in the sacrificial service there. They were still taking their Pesach lamb each year to the Temple, then roasting it at home and gathering for the seder. How could they say the berachah (blessing) over the cup at Pesach, and still participate in the drinkfests of pagan worship? How could they eat the Pesach lamb and yet commune with those who celebrated the pagan gods? The two are mutually exclusive. Thus, the “table of demons” most obviously refers to the eating of pagan sacrifices. In contrast, the “Lord’s Table” refers to eating the sacrifices offered to HaShem, (such as the peace or thank offering), perhaps most particularly the Pesach sacrifice.

Interestingly, another Talmudic reference (in addition to Avot 3.3 quoted above) parallels the term “table” with “altar” (b. Betsah 20b). In this discussion, the Sages consider the halachah of the Shammites, who refused to offer free will and votive sacrifices on festival days, since in their opinion this would be contrary to the Sabbath prohibition of work, while the Hillelites permitted and encouraged such sacrifices on festival days. Abba Shaul argues, .” . . is it logical that your table should be full while your Master’s table lies barren?” What is the Master’s table in Abba Shaul’s argument? It is the altar, as Num. 28:2 indicates, “Command the sons of Israel and say to them, ‘You shall be careful to present My offering, My food for My offerings by fire, of a soothing aroma to Me, at their appointed time.’ Thus, in the Talmudic discussion, “table” is used as a reference to the altar. If in the festival one sits down to enjoy a feast, it is also reasonable that one should offer sacrifices on the altar of God, i.e., give to Him a meal to enjoy.

The idea of “table” as parallel to “altar” fits with the larger context of 1 Cor 10. Rather than viewing the phrases “cup of the Lord” and “table of the Lord” through the lenses of the later custom of the Eucharist, we should understand Paul’s concern about those who felt comfortable participating in both the sacrifices of the Temple and those of pagan ceremonies. As the next chapter shows, the sacrifice which stood predominant in Paul’s mind is the Pesach, to which I will now turn my attention.

1 Corinthians 11

The larger context of this section is obviously dealing with halachic matters put forward by the fledgling Corinthian church. Issues of legal arbitration (ch. 6), marital relations/divorce (ch 7), purities of food and contact with Gentiles (ch. 8), support of teachers (ch. 9), issues relating to idolatry (ch. 10), matters relating to corporate worship/hair styles (ch. 11), and use of spiritual gifts (chs. 12-14) are addressed. The early Messianic congregations had many new situations and they were seeking halachic decisions from those whom Yeshua had appointed as His shelachim (apostles).

The more immediate context of chapter 11, then, is the issue of corporate worship—how believers, i.e., men, women, Jew, and non-Jew should worship together without hindering each other. Eating together was naturally included in corporate worship, for it was at common meals that many of the halachic issues arose.

The scene Paul describes in 11:20-34 has the following elements: (1) a meal is scheduled for the congregation, (2) not everyone is able to arrive at the same time, (3) some feel compelled to begin before everyone has arrived, (4) there is sufficient wine to result in some being drunk, and (5) the meal is connected to the final Pesach that Yeshua ate.

While Paul could be describing the Agape meal established by the early church (cf. Jude 12), it seems just as reasonable to me that he is describing the yearly Pesach seder. First, since Yeshua had made such a significant addition to the seder by proclaiming His death and resurrection to be the point of the 3rd cup and broken matzah, the Pesach became a central festival in the early church. Even as late as the 4th century the Church leaders were arguing about when to celebrate Passover. Thus, though the Pesach had been celebrated for millennia, Yeshua’s pointed words at His last seder rendered the Pesach the “Lord’s Supper” to the Messianic community.

Secondly, the time at which one actually eats the Pesach seder was an issue in the 1st century Judaisms. The Torah command, that the Pesach be slain בֵּין הָעַרְבָּיִם, “between the evenings” or “twilight,” was variously interpreted by the Sages due to differing opinions on what was meant by “between the evenings.” Their basic question was simply to which day twilight belonged. Some thought it belonged to the day that follows (m. Shabb. 19.5), others thought it belonged part to the preceding day and part to the day that follows (m.Keritot 4.2), while still others ruled that it belonged entirely to the day that followed (m. Niddah 6.14; m. Zavim 1.6). While it appears that this last interpretation eventually won halachic standing, it is apparent that in the 1st century the issue was being disputed. We should expect, then, that there would be disputes about how to fulfill the Torah commandment which stated that the Pesach must be slain at “twilight on the 14th of Nisan.”

Furthermore, the Sages were time conscious about the Pesach festival. For instance, the leaven had to be burned no later than 11:00am on the 14th (m. Pes. 1.4), occupational work ceased by noon (m. Pes. 4:5), daily sacrifices were minutely scheduled (m. Pes. 5.1) as was the slaughter of the Pesach lamb (m. Pes. 5.3ff). The lamb was roasted as soon as it was dark (m. Pes. 5.10) and, since nothing of it could be eaten after midnight (m.Pes. 10.9; cf. Ex 12:10, [the Sages considered midnight the dividing between night and morning]), one can imagine that the Jewish believers were anxious to begin the meal as soon as possible after the roasting was completed, especially since the seder itself was fairly involved. (The Mishnah shows that the seder of the 1st century contained many of the essential elements comprising our modern day Pesach seder.) One can also imagine that non-Jewish believers may have had to come very late to the Pesach seder, since their Roman or Greek masters were not observing the festival. Rather than waiting as long as possible, the Jewish believers, anxious to get the seder underway, started before the non-Jewish believers could arrive. By the time they did come, the seder was finished, including four cups of wine!

It appears that the excuse of hunger was given by those whom Paul rebukes (v. 34). This may sound like a feeble retort at first, until one realizes that the Mishnah records a rabbinic ruling which forbade eating between the time the Pesach lamb was slain, and the seder meal began (m.Pes. 2.1; 10.1). Moreover, the Mishnah is full of laws concerning sacrificing the Pesach lamb for a group, and who may participate in eating that lamb and who may not (m. Pes. 8.3, 6, 7; 9.9). But all who will be eating of a single Pesach sacrifice must be declared before the sacrifice takes place (m.Pes. 8.3). Thus, eating would begin when those who had been declared as participating arrived. Late-comers could easily be left out.

Paul, having established the fact that the Pesach seder could now be celebrated with not only redemption from Egypt in mind, but with eternal redemption as the ultimate emphasis, exhorts the Corinthians to live out the redemption which was theirs through faith in Yeshua. This means practicing the kind of forbearance and love toward others which Yeshua displayed towards them. Rabbinic laws, while not bad in and of themselves, were contributing to the division of Jew and non-Jew, and this, for Paul, was a denial of the oneness Yeshua had purchased with His own blood. Man-made laws were not as important as love. The Messianic community was to function as a family at the Pesach, waiting for each other and displaying a true sense of agape, the kind of love which would mark them as Yeshua’s disciples (Jn 13:34, 35).

1 Corinthians 11:20ff is about Pesach, not a new institution of the 2nd century church called the “eucharist.”

There are, in fact, hints that the evolution of the Eucharist out of the Pesach seder was happening in the late first century and even earlier. Putting aside the date of the final form of the Gospels (a subject outside the scope of this essay), it is interesting to note that Matthew, Mark, and John record the ceremony in the order “bread” followed by “wine,” while Luke alone narrates the order as “wine” followed by “bread.” Luke’s mention of the second cup after the bread (Lk 22:20-21) follows the pattern of the Pesach seder, yet this section is missing and/or changed in a number of the early manuscripts (Codex D, Syriac, Italic, Coptic, etc.) so as to conform to the order “bread” followed by “wine.” Paul likewise has the order “bread” followed by “wine,” though he explicitly mentions the cup to be “after supper.” Apparently he concerned himself only with those two aspects of the seder to which Yeshua made direct, redemptive reference. Similarly, The Manual of Discipline, a non-biblical document found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, specifically commands the community to engage in a ceremony in which the priest first blesses the bread and then the wine (VI 4-6). This is an interesting parallel because whomever the Dead Sea Scroll peoples were, they had removed themselves from Jerusalem and had formed new rituals in their exclusivistic society.

In contrast, the Didache, an early document (late 1st or early 2nd century) purporting to contain the teachings of the Twelve Apostles, has the order “wine” followed by “bread”:

But as touching the eucharistic thanksgiving give ye thanks thus. First, as regards the cup: We give Thee thanks, O our Father, for the holy vine of Thy son David, which Thou madest known unto us through Thy Son Jesus; Thine is the glory for ever and ever. Then as regards the broken bread: We give Thee thanks, O our Father, for the life and knowledge which Thou didst make known unto us through Thy Son Jesus; Thine is the glory for ever and ever. (from Lightfoot, Apostolic Fathers, Didache 9, p. 126).

What might this all suggest? It might strengthen the idea I have offered, that the church, as she moved further and further from her Jewish roots, sought to extract from the Pesach seder (which she no longer wanted to celebrate) those very important words of Yeshua paralleling the wine with His blood, and the bread with His flesh. In so doing, she created a new ceremony in which only the two elements of the seder remained. Since Yeshua had first singled out the bread as typical of His broken body, the church put that element first, and followed it by the cup. She was able to take an intrinsically Jewish ceremony and divest it of any connection to its Hebrew origin, thus making it her own. Once it was distinctively hers, she could add to it without restraint, making it the central and all-important institution of the church by which heretics and believers were distinguished. Today in the Roman Catholic church, excommunication means first and foremost that a congregant is denied access to the eucharist. Likewise, in many Protestant denominations, church discipline consists of, in part, prohibiting that person from participating at the Lord’s Table, making it the central and all-important institution of Christian fellowship.

What then, as Messianic believers, should our position be on celebrating and/or participating in the Lord’s Table? I would suggest several things for your consideration. First, it is a shame that the church has attempted to replace Pesach with the Lord’s Table. Celebration of the yearly festival of Passover is a Torah commandment, and ought to be kept by all who name Yeshua as Lord. It, far more than the eucharistic ritual, gives the fuller picture of Yeshua’s death and provision of redemption by His death. While there is nothing wrong in remembering the work of Yeshua whenever one eats, it is wrong to neglect a festival which God gave to His people. Secondly, the doctrine of transubstantiation (that the bread and blood actually turn into the flesh and blood of Mashiach) is wrong and dangerous, and denies the essence of true salvation in Yeshua. Participating in a ceremony which teaches such a false doctrine is clearly wrong. But thirdly, I see nothing wrong with eating bread and drinking juice to remember the death of Yeshua. The celebration of the Lord’s Table in and of itself is not wrong. In fact, it can be spiritually rewarding. One could only hope, however, that the yearly Pesach celebration would be the capstone in the church’s life as she celebrates the death and resurrection of Yeshua and that the celebration of the Lord’s Table would always find both its origin and its conclusion in this yearly celebration.