Background

On Shabbat I worship at Beit Hallel, a messianic congregation in Tacoma. As one of the teachers in this congregation, I field questions and concerns, especially from those who regularly visit our services or festival celebrations. Usually the questions of on-lookers have to do with Judaism in general, and the matters of the Torah in specific. It is not uncommon, however, to be asked about Paul’s instructions in 1Cor 11 and how we justify men wearing Kippot or Yarmulkes (the Yiddish equivalent).

Recently I was asked to listen to a message delivered by a popular radio preacher who was teaching a series on 1 Corinthians. What troubled the person who suggested I listen was the manner in which this radio teacher belittled Jewish men for wearing “beanies” on their heads when they came into a synagogue. (He informed the people that the word “they” use for these “beanies” is too difficult to pronounce.) He went on to teach his listeners that Jewish men wear something on their heads as a sign of shame and guilt, which is why Paul, in 1Cor 11, commands the Christian men not to wear anything on their heads—they’ve been forgiven by the blood of Christ. Obviously, anyone believing what this teacher said and then visiting Beit Hallel would be either very confused or very put-out, because “beanies” abound!

Aside from the somewhat off-handed mannerisms of this radio preacher, the fact remains that if Paul commands men not to wear anything on their heads when praying or prophesying, then Jewish or not, those who follow Yeshua as Messiah should follow the halachah of His apostle. The issue is, does Paul, in fact, prohibit a man from wearing anything on his head when he prays in the assembly?

A number of questions immediately arose in my mind. (1) Was the Corinthian congregation exclusively Gentile, or was there a Jewish constituency in the Christian community? If there were a strong Jewish segment of the Corinthian congregation, was it a 1st Century practice for men to cover their heads in the place of worship, or was this only a later custom? What about the tallit (prayer shawl)? Was it customary in the 1st Century to put the tallit over the head while praying? (2) If Paul is prohibiting a man from wearing anything on his head while worshipping in prayer or prophecy, what about the priests who wear hats when they minister in the Temple? And, if the priests wear hats as instructed by God Himself, how could an argument from the creative order of male and female be used to ban headgear for men? (3) What is the terminology for “veil” or “covering”? Why is Paul concerned about a woman’s hair if he expects it to be covered? Why does he end the argument by stating that a woman’s hair is given to her “for a covering,” where the Greek word translated “for” is ἀντί, anti, which often has the meaning “instead of” if all along he has commanded the woman to wear a covering?

1. Was the Corinthian congregation primarily made up of Gentiles or was there a significant Jewish element within the congregation?

The question of whether or not there was a Jewish constituency in the Corinthian congregation is an important question for a number of reasons. First, a Jewish presence in the assembly would automatically mean that Jewish questions would be raised in any halachic discussion. The subject of 1Cor 11 would certainly fall in this category. Secondly, one would presume that members of the community would make trips to Jerusalem for festivals and other important days, strengthening the ties with the Temple and the functioning priesthood there. Finally, Paul does not differentiate between Jews and Gentiles when it comes to obeying God. He did not see two standards of living, one for Gentile and another for Jewish believers. Thus if Paul considered it inappropriate for men to wear something on their heads while praying, his ruling would apply equally to Jews and Gentiles.

The history of Corinth and her population is not completely clear. Philo, in mentioning Corinth by name, might well imply a strong Jewish population there. Acts 18:2 might indicate that Jews fled to Corinth when Tiberius expelled them from Rome in 19 C.E. We know that a synagogue existed in Corinth (Acts 18:4) and a lintel from a synagogue doorway has been recovered.

Bauer had suggested that the division in the Corinthian congregation was between Jewish and Gentile factions, but this view was mostly abandoned in subsequent years for a theory that the opponents comprised some form of early Gnosticism. Schmithals suggested that they were Jewish Christian Gnostics.

We know that there were non-Jews in the Corinthian congregation, for Paul makes reference to their idol-worshipping days (1 Cor 12:2). Likewise, it seems highly unlikely that Paul would spend the amount of time he does (1Cor 8-10) on a discussion of meat offered to idols if the group to whom he was writing was primarily Jewish. Yet there is every indication that a Jewish population was also extant in the congregation at Corinth. Apollos, a Jew from Alexandria, was one of the recognized teachers. Likewise, Aquila and Priscilla, a Jewish couple according to Acts 18:2, arrived at Corinth shortly before Paul’s visit. Moreover, the epistle is full of language and themes that parallel the Judaisms of Paul’s day. Appeal is made to the Torah in supportive ways, as is the use of “tradition” as a binding aspect,

Indeed, Tomson has shown that the epistle contains a great deal of Jewish traditional law and that in many instances Paul is establishing halachah for the Messianic community after the pattern of Jewish halachah. Paul appears to quote Ben Sira (Sir 37:28) in the twice repeated “all things are lawful, but not all things edify,” a work which enjoyed wide rabbinic discussion.

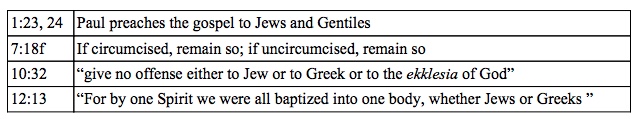

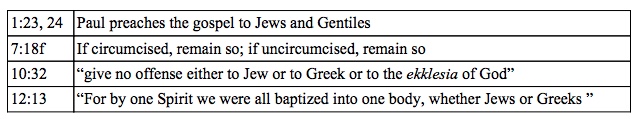

The text itself also suggests the presence of a significant Jewish segment in the Corinthian congregation. Note the following:

Summary

It appears most likely that there was, in fact, a Jewish presence in the congregation at Corinth and from this we ought to conclude that Paul would have taken this into account as he structured the halachah of worship for the assembly.

2. What was the common practice of Jewish men in 1st Century synagogue worship? Was it traditional to cover the head with some kind of hat or with the tallit (prayer shawl)?

Once we have accepted the fact that there was a Jewish constituency in the congregation at Corinth and that it therefore continued to function as a synagogue community, it seems logical to ask whether or not the men would have covered their heads in worship as a matter of their Jewish tradition.

We may begin by reminding ourselves that the priests in the Temple were required to wear a turban of cloth on their heads, the High Priest having an additional golden plate, called a צִיץ (tzitz, “ornament”?) and described as נֶזֶר (nezer, “crown”) attached to the band of the miter with a cord of techeilet. Obviously, these priestly garments were in use during the 2nd Temple period. On this fact alone it seems incredible that Paul would argue on the basis of the created order that men wearing something on their heads while engaging in worship are doing something dishonorable. Murphy-O’Connor agrees:

Since Paul grew up in a tradition where priests prayed with turbans on their heads, it is impossible to imagine him being disturbed to the extent indicated by the emotional tone of this passage simply because a man prayed with something on his head.

The tallit or prayer shawl has its roots in antiquity, though most likely the four-cornered garment to which the tzitzit (צִיצִת, tzitzit) were attached was simply the common outer garment warn by men in the ancient Near East. The commandment of Num 15:37-41 instructed Israel that tassels or tzitzit were to be worn on the four-corners of the garment (cp. Deut 22:12). It was common in ancient societies for men to wear the outer garment wrapped around the body with the access thrown over the left shoulder. On the “Black Obelisk” of Shalmaneser III (858-824 BCE), Jehu king of Israel is shown wearing a fringed outer garment with tassels on a section thrown over the shoulder. Oesterley suggests that the “hem” of Yeshua’s garment which the woman with the flow of blood touched (Matt 9:20, cf. 14:36) was a similar garment with fringes attached. Such an outer garment (אֲדֶרֶת, aderet) was large enough to cover the head (1 Ki 19:13), and in some instances carried with it the symbol of office or power, as in the mantle of Elijah (1Ki 19:19).

In 1st Century Israel the Roman citizen was allowed to wear the toga, a large, semicircular garment draped around the body. Often, however, only the wealthy could afford such a cloak. The Greek himation was the more common outer garment for men and women, including the Roman citizens.

Color and design of the himation distinguished the male and female variety, along with stripes of different widths and color which ran around the edge which draped the neck. Yadin discovered garments of this type in the Cave of Letters near the Dead Sea which he dated ca. 90-135 CE, as well as wool dyed with techeilet for use in the tzitzit. He argues that the stripe framed the face when the himation was pulled over the head for prayer or sacrifice. Similar garments have been found at En-Gedi and on some of the clothing piled and burned by the last defenders of Masada.

The Rabbinic sources indicate that the tallit was wrapped around the worshipper while praying. The story is told of Mordechai, who when he saw Haman coming toward him, wrapped himself in his tallit and stood before the Holy One in prayer. In another place the Midrash asserts that the Rabbis and Sages are known by their wrapping themselves in tallitot. This most likely accords with Matt 23:5 where Yeshua rebukes the Pharisees for broadening their tefillin and lengthening their tassels. The Midrash indicates that the tallit with its fringes was a mark of privilege and office and could denote rank or act as a mark of piety. The Talmud explains that the wearing of the tassels distinguished between a haver and the am ha-aretz.

Hurley states it in these terms when discussing the common four-cornered garment to which was attached the fringes:

This garment, the Tallith of the Talmud and modern Judaism, was spread as a sign of reverence over the head of a Jewish man when he prayed and over a body in the grave. The purpose was that the person might “appear white before God.” A similar understanding of purity, white garments, and reverence may be seen throughout both Testaments.

Lightfoot claims that the act of covering one’s head while praying had a twofold significance: (1) showing reverence to the Holy One, and (2) to show oneself ashamed before God and unworthy to look upon Him. He bases his idea of a covering denoting shame from the Aramaic rendering (in Onkelos) of Hebrew בְּיָד רָמָה, (b’yad ramah) “with a high hand.” Onkelos has בריש גלי, “with an uncovered head.” From this it is deduced that a covered head must denote “ashamed, without confidence.” Jastrow suggests that the meaning of the Aramaic phrase בריש גלי is simply “openly,” making the converse to be “privately.” In fact, while the tallit may be used in prayers of repentance and sorrow, there is no indication that its primary meaning when covering the worshiper was to portray him as “ashamed.” Rather, just the opposite is true. Elbogen writes:

The covering of the head during prayer was related to the wearing of the tallit, which had a hood attached to it. It was understood as an expression of submissive respect for the divine majesty; it was also seen as the privilege of a free man that he could remain with covered head. It is Israel’s privilege to participate in the revelation of the King of kings [that is, the Shema‘] sitting comfortably with covered head, while the servants of earthly powers must hear all royal proclamations bareheaded in fear and trembling.

The rabbinic comments which relate the wrapping of oneself “in fear” (Aramaic אָימה; Hebrew יִרְאָה) should be understood in the sense of “fear of God,” that attitude of coming before a great and might King. To suggest (as Lightfoot does) that Paul prohibits men from worshipping with heads covered because now, as the redeemed of Christ, they no longer need to be ashamed, is to miss the point. From a Jewish perspective, prayer is an invitation to communion with the King, and such communion should be entered in בִּעֵת רָצוֹן, at an appropriate time, and בְּיִרְאָתֶךָ, in awe of You.

Thus, the rabbinic sources take the general view that covering one’s head while praying, whether with hat or tallit, is a sign of respect to God in Whose presence the congregation has gathered. The Talmud gives this viewpoint:

Rav Huna did not walk four amot bareheaded; he would say, ‘The Shekhina is above my head.’ Cover your head so that reverence for God be upon you

Furthermore, as far as the Talmud is concerned, it would have been the norm for a person reciting the Shema‘ to cover his head with the tallit. In a discussion of what constitutes an interruption in the reciting of the Shema‘ such that one needed to begin again, the Talmud notes:

And R. Hanina said, ‘I saw Rabbi [while reciting the Prayer] belch and yawn and sneeze and spit and adjust his garment, but he did not pull it over him; and when he yawned, he would put his hand to his chin.’”

The interpretation given to the phrase “he did not pull it over him” by Rashi is that “he did not pull it over him if it fell off his head while reciting the prayer, for this would constitute an interruption.” R. Hananel suggests, however, that the interpretation should be that “he arranged his garments so that the tallit would not fall off of his head.” Whatever the case, having the head covered with the cloak (tallit) was taken as normative for reciting the prayers. The actual phrase in question is אבל לא היה מתעטף, but he did not cover himself.”

Summary

There appears to be sufficient evidence to suggest that covering the head while praying was not uncommon for men in the early centuries of the Common Era. Though it may not have been a universal ruling in the throughout the wider Judaisms as became the case in later times, it was, nonetheless, practiced by Jews in their places of prayer and was common enough to be considered traditional. As such, we should attempt to see how Paul’s directives in 1Cor 11:2-16 can be understood in light of the synagogue setting of the Corinthian congregation and the traditions they doubtlessly practiced.

3. What is the terminology that Paul uses to describe the “veil” or “covering” in 1Cor 11:2-16?

It is beyond the scope of this paper to consider the entire passage of 1Cor 11:2–16 and the exegetical problems it presents. My specific purpose here, however, is to look at the terminology which is universally translated by such words and phrases as “have something on the head,” “uncovered”, “covered”, “veil”, “head covering”, etc.

We may begin in verse 4. The NASB translates:

“Every man who has something on his head while praying or prophesying, disgraces his head.”

The Greek for “has something on his head” is κατὰ κεφαλῆς ἒχων, “having down from the head.” First, note that there is no direct object for the verb ἒχω and thus the supplied “something” of the NASB. In fact, nowhere in this passage is the noun for “covering” or “veil” used except in v. 15, where Paul says that “her hair is given to her for a covering” (ἡ κόμη ἀντὶ περιβολαίου δέδοται [αὐτῇ]). Murphy-O’Conner, after noting the 12 other times Paul uses κατά with the genitive, concludes that “it [is] unlikely that he would have employed this preposition with the genitive to designate something ‘resting upon’ the head.” It would be preferable to retain the regular sense of κατα with the genitive unless something in the context suggests otherwise. This normal usage would suggest an “adversive” sense, and with regard to motion, movement away from.

Most translators, however, look to v. 7 to find a direct object for the “dangling” ἒχω of v. 4. Seeing in the verb κατακαλύπτεσθαι the sense of “covering upon,” the gap is filled in for v. 4 to make the two verses parallel. The καλύπτω word group, however, needs to be investigated more closely.

If we look first to the Lxx we can see the range of meaning afforded Paul as he used this term with which he was familiar. Leviticus 13:45 describes the signs which publicly show a leper to be unclean. One of these is loosed hair. The Lxx renders the Hebrew ַפָּרוּעַ (paru‘a) by ἀκατακάλυπτος, the same word used in 1Cor 11:5 rendered “uncovered” by most translations. Here is a valid parallel which shows that the noun ἀκατακάλυπτος could be referring to hair that was let down. The Talmud uses the same Hebrew term, ַפָּרוּעַ, to describe long hair on a priest which was forbidden under penalty of death.

The Mishnah clearly teaches that it was forbidden for a woman to be in a public place with her hair down. In fact, such an act was grounds for divorce:

And these are they that are divorced without their marriage settlement: she who transgresses the Law of Moses and Jewish custom … And what is here meant by Jewish custom?—If she go forth with her hair loose [יוֹצְאָה וְרֹאשָׁהּ פָּרוּעֵ].…

Furthermore, a shorn woman was despised, since the cutting of the hair was considered a sign of object uncleanness. In a Mishnah concerning the right of a husband to annul the vow of his wife, we read:

… but concerning the cutting off the hair in uncleanness he may nullify, because he may say, ‘I have no pleasure in an untidy woman.’ Rabbi says, He may absolve even in the case concerning the cutting off the hair in cleanness, since he may say, ‘I have no delight in a shorn woman.’

The Lxx of Numbers 5:18 may also be instructive for our study. In the water ordeal for a woman accused of adultery, the Torah commands וּפָרַע את־רֹאשׁ הָאִשָּׁה, literally) “let go the woman’s head.” The Lxx reads και ἀποκαλύψει τὴω κεφαλὴν τῆς γυναικός, utilizing the same καλύπτω word-group found in 1Cor 11. Hurley states that

ἀκατακάλυπτος occurs only in the adjectival form. Verbal forms of פָּרַע must therefore be rendered by alternative verbs. The Greek translator of this section has chosen ἀποκαλύπω.

Here we have an indication that in the Hebrew culture a woman with hair kept up on her head was marked as married and under the authority of her husband. Letting her hair down in the water ritual marked her as indecent in her relationship of marriage. If she were found innocent, her hair would again be put upon her head. Once again, the Mishnah corroborates this cultural custom. In a section dealing with marriage settlements, the dispute of whether a woman was wed as a virgin or not is settle by consideration of her hair as she was carried to the ceremony:

If a woman became a widow or were divorced and says, ‘Thou hast wed me as a virgin,’ and he says, ‘Not so, but I wedded thee when thou was a widow,’ if there be witnesses that she had gone forth in the virginal bridal litter and with the hair of her head loose [פָּרוּעַ] her marriage settlement is two hundred.

Hair which was loose or disheveled marked an unmarried woman. Conversely, a married woman maintained her hair braided upon her head as a sign of her position as a wife in the community. The Talmud records the testimony of a pious mother of two priests who confessed that “the beams of my house have never seen my bare head.” If it is wrong to go out in the street with one’s hair loosened, then the fence around the Torah would be to always have one’s hair up in braids. Such was the thinking of this pious woman.

The data thus far gathered gives a basis for suggesting that what Paul is dealing with in this entire passage is hair and not head coverings. ἀκατακάλυπτος of v. 5 would correspond to the same word used by the Lxx in Lev. 13:45 for hair that is let down. Conversely, κατακαλύπτομαι of v. 6 would envision a woman with her hair upon her head, a symbol of the authority she has as a married woman (v. 10). A man, however, is not allowed to have long hair, whether hanging loose or braided (v. 7). In a pagan culture where long hair on a man was a sure mark of sexual deviency, this is understandable. It would seem clear that Paul considered the Nazerite vow to be an exception.

That Paul has hair length on his mind is evident from the passage. In v. 6 he contrasts the woman who has her hair loosened with the woman who has her head shaved. This is understandable if loosened hair was, in the Hebrew culture, a public announcement of virginity and in that sense a statement of availability, while at the same time a woman whose head was shaved was one who was, for one reason or another, dishonorable. V. 14 puts the idea of man’s long hair in juxtaposition with a woman whose hair is let loose, both of which are undesirable. V. 15, however, suggests that a woman’s long hair (κόμη), when braided up on her head, functions for her in the place of a cloth for covering. It seems quite possible that Paul’s concern in this passage is how men and women wear their hair, and what the hair-styles say within the culture.

Martin has made an interesting suggestion by noticing that there are two forms of the imperative used in v. 6, one aorist and one present. He shows that Paul consistently uses the present imperative to denote an action of unlimited extension or habitual occurrence, while the aorist is used to describe a specific action, limited in duration. Considering that there might well have been those converts who entered the assembly with shorn heads, Martin suggests this translation:

For if a woman is not covered (does not have long hair) then let her remain cropped (for the time being; κειράσθω, aorist imperative with cessative force, referring to a particular situation), but since it is a shame for a woman to be cropped or shorn let her become covered (i.e., let her hair grow again; κατακαλύπτεσθω (present imperative for a non-terminative, inchoative action).

Finally, in v. 15 Paul states unequivocally that a woman’s long hair takes the place of a head covering, περιβολαίον (“cloak,” “covering,” “wrap”) being the only time in the entire section an actual piece of clothing is mentioned. This is in contrast to v. 14 where a man is not to have “long hair” (κόμη).

Summary

Several indications show beyond reasonable doubt that Paul is using κατακαλύπτω and related terms to refer to long hair. First, he uses it in contrast to the man who is forbidden to have long hair (v. 4, 14). Secondly, he contrasts ἀκατακάλυπτω with being shorn. There is only one antithesis of being shorn, that is to have long hair. Covering a shorn head does not negate its state of being shorn. On the parallel with the Lxx use of this word, as well as the cultural aspects of women’s hair in the Hebrew society, it seems most probable that the meaning is “loosed,” “hanging down,” which is what Paul prohibits for the man. Thirdly, nowhere in the passage is any word used for a material veil or head-dress, except in v. 15, where the woman’s hair is said to be given in the place of that item of dress. Fourthly, since the forms of the verb κατακαλύπτω found in vv. 6 and 7 are not constructed with an indirect object, it is best to take them as passives. Finally, if a piece of cloth or veil is what Paul had in mind, one would expect him to use some more explicit term for “unveiled,” such as γυμνοκεφαλος, “bear-headed,” on the analogy of “bear-footed” as in ἐν τριβόλοις γυμνοῖς ποσὶ περιπατεῖν, “to walk barefooted among thorns.”

Conclusion

Paul is not referring to head coverings in this passage. As such, he was not requiring the congregation at Corinth to abandon the Jewish tradition for men to cover their heads when praying. He was, however, reinforcing a Jewish perspective on the husband/wife relationship in which the wife receives a position of authority in the community by virtue of her marriage relationship. He also was stressing the importance of marking the distinction between male and female and the God-given roles each is to perform within the believing community.

Bibliography of Materials Consulted

Articles & Individual Studies

Daube, D. “Pauline Contributions to a Pluralistic Culture” in Jesus and Man’s Hope, D. G. Miller & D. Y. Hadidian, eds., Pittsburgh, 1971.

Derrett, J. Duncan M. “Religious Hair” in Studies in the New Testament, E. J. Brill, 1977.

Edwards, Douglas R. “Dress and Ornamentation” in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, 6 vols., Doubleday, 1992.

Hooker, M. D. “Authority on Her Head: An Examination of 1 Cor XI.10,” NTS 10, 410-16.

Hurley, James B. “Did Paul Require Veils or the Silence of Women? A Consideration of 1 Cor 11:2-16 and 1 Cor 14:33b-36,” WTJ 35(1973), 190-220.

Martin, William J. “1 Corinthians 11:2-16: An Interpretation” in Apostolic History and the Gospel, Gasque, W. Ward and Martin, Ralph P., eds., Eerdmans, 1970.

Murphy-O’Conner, Jerome. “The Non-Pauline Character of 1 Corinthians 11:2-16?,” JBL 95/4 (1976), 615-21.

Murphy-O’Conner, Jerome. “Sex and Logic in 1 Corinthians 11:2-16,” CBQ 42(1980), 482-500.

Murphy-O’Conner, Jerome. “1 Corinthians 11:2-16 Once Again,” CBQ 50(1988), 265-274.

Oster, Richard. “When Men Wore Veils to Worship: The Historical Context of 1 Corinthians 11.4,” NTS 34(1988), 481-505.

Thompson, Cynthia L., “Hairstyles, Head-Coverings, and St. Paul: Portraits from Roman Corinth,” BA 51.2 (June, 1988), 99-115.

Walker, Wm. O. Jr. “1 Corinthians 11:2-16 and Paul’s Views Regarding Women,” JBL 94, 94-110.

Walker, Wm. O. Jr., “The Vocabulary of 1 Corinthians 11:3-16: Pauline or non-Pauline?,” JSNT 35(1989), 75-88.

Walke, Bruce K. “1 Corinthians 11:2-16: An Interpretation,” BibSac 135:537, Jan-Mar, 1978.

Weeks, Noel. “Of Silence and Head Covering,” WTJ 35(1973).

Wilson, Kenneth T. “Should Women Wear Headcoverings?” BibSac 148:592, Oct-Dec., 1991.

Ziderman, Irving. “First Identification of Authentic Tekelet,” BASOR 265, 25-33.