Articles

Traditional Understanding

Discussions on the place of Torah in the believer’s life often surface other, significant issues. One of these is the question of spirituality. Specifically, since the coming of Messiah Yeshua and the giving of the Spirit at Shavuot (Acts 2), have we moved to an era of greater understanding and spirituality than what the believers of ancient Israel experienced? Did the coming of Yeshua advance us in matters of spirituality over those who lived before His coming? And does the Spirit of God work in greater and more significant ways today than He did in the generations before Yeshua’s appearance?

The reason this question arises in discussions of Torah-life is obvious: if we have arrived at a time when the work of the Spirit is greater, and therefore when believers have a greater measure of spirituality than those in ancient Israel, then we have also arrived at a time when something greater than Torah exists for the people of God. The conclusion is also obvious: to teach that the Torah is for us today appears to be taking steps backwards—to be overlooking the greater level of spirituality we now possess and settling for the inferior spirituality possessed by those during the era of the “old covenant.”

Usually those who think we have arrived at a greater spirituality suggest the following as support:

“Truly I say to you, among those born of women there has not arisen anyone greater than John the Baptist! Yet the one who is least in the kingdom of heaven is greater than he. “From the days of John the Baptist until now the kingdom of heaven suffers violence, and violent men take it by force. “For all the prophets and the Law prophesied until John.

Verses like these show that though the prophets had much to teach us, the words of Yeshua and even of John are greater and filled with more spiritual power.

4. But perhaps most telling is the simple fact that the Spirit now works in ways He never did before. He equips every saint; He indwells every believer, not on a temporary basis as He did with a few select individual in ancient Israel, for the Spirit now indwells all believers eternally; He fills the believer with His presence and equips each one to function in the body of Messiah by knitting each one to the other in a community which far surpasses the community of ancient Israel. In fact, nothing stands as a greater proof of the higher level of spirituality we enjoy today than the obvious new work of the Spirit in the New Covenant as opposed to His somewhat temporary and sporadic work in the Old Covenant. If there were nothing else, this alone should teach us that we have a level of spirituality that far exceeds that enjoyed by the saints of old. Consider these verses:

John 14:17 that is the Spirit of truth, whom the world cannot receive, because it does not see Him or know Him, but you know Him because He abides with you and will be in you.

John 7:39 But this He spoke of the Spirit, whom those who believed in Him were to receive; for the Spirit was not yet given, because Jesus was not yet glorified.

Response

The idea that spirituality after Yeshua far exceeds that before Him is based upon a number of misunderstandings.

The first issue that should be addressed is the misunderstanding of the labels “old covenant” and “new covenant.” Contrary to the popular use of these terms, they do not describe “dispensations” or “periods of time.” While the normal understanding is that the “old covenant” describes the life of God’s people before the coming of Yeshua, and the “new covenant” describes their life after the coming of Yeshua, no such definition can be found in the Scriptures. Often the traditional viewpoint uses “old” and “new” covenant to describe the Tanach (the Scriptures of God’s people before the coming of Yeshua) and the Apostolic Scriptures (the Scriptures of God’s people after the coming of Yeshua). Once again, there is no biblical basis for viewing the Hebrew Scriptures as the “old covenant” and the Apostolic Scriptures as the “new covenant.”

Then what do the labels “old covenant” / “new covenant” mean? The “new covenant” is a nationalistic covenant made with the House of Israel and House of Judah in which the Torah of Sinai will be written upon their hearts, and for the first time in history the nation of Israel will be loyal to her God through faith in His Messiah, Yeshua. This covenant is based upon faith through which is obtained the forgiveness of sin (Jeremiah 31:31-34).

The “old covenant” (used only one time in Scripture, 2Corinthians 3:14) is an expression used only by Paul to refer to a Jewish person who reads the Tanach apart from the illuminating work of the Spirit. When this occurs, the Jewish reader does not see Yeshua in the Tanach because a veil lies over his heart. As long as he reads the Tanach as mere letters without the illuminating work of the Spirit he will never see the Messiah of Whom the Prophets spoke, and the Tanach does not lead to salvation. But when these same Scriptures, the Torah, Prophets, and Writings, are read with the veil removed by the Spirit, then these same words show him Messiah, and bring Him to saving faith. Without the Spirit the Tanach is the “old covenant,” but with the Spirit the Tanach leads to Messiah, the Torah is written on the heart, fulfilling the promise of the “new covenant” (cf. Jeremiah 31:31-34).

So the writers of Scripture did not define “old” and “new” covenants as successive eras or generations, the “old covenant” being “back then” and the “new covenant” being “now.” Furthermore, for Paul, the “old covenant” is viewed as condemning, without faith in Messiah Yeshua. No one who is a member of the “old covenant” is saved. All who are in the “old covenant” are condemned because they are without faith.

Furthermore, Jeremiah’s “new covenant” is nothing more than the realization of the Mosaic Covenant on a national scale, for it is characterized by the phrase “I will write the Torah upon their hearts.” The very Torah that Israel rejected will, in the “new covenant,” be written on Israel’s heart by the Spirit. What is “new” or “unique” about this covenant is that its fulfillment will mark the only time in history when the nation as a whole walks by genuine faith in the Messiah.

So what is promised in the “new covenant” is the very thing that the remnant experienced throughout the history of Israel, i.e., genuine faith in God and in His Messiah, resulting in the Torah being written upon the heart (=becoming a reality in one’s life). Paul makes it clear that a remnant of true believers has existed in every generation (Romans 11:1ff). They must have, therefore, participated in the faith which Jeremiah prophesies for the whole nation in the future. This remnant, including Gentiles who have been attached to Israel through their saving faith, thus participate in the “new covenant” as the first fruits of the final harvest.

The “new covenant,” then, will not be fully realized until the House of Israel has the Torah written on the heart, from the least to the greatest, and all will be loyal to (=know) God. Until that happens, the remnant in each generation participates as the first fruits, being members of the “new covenant” which awaits its final closure in the salvation of the entire nation of Israel.

This being the case, the “new covenant” cannot be something that awaited the coming of Yeshua (though surely His saving work is the means by which the “new covenant” will be fully realized). Those who by faith looked forward to the coming Messiah and trusted in Him for their salvation were as much members of the “new covenant” (as first fruits) as the nation of Israel will be in the end of days when she has the Torah written upon her heart. The “new covenant” is therefore not time-bound. Wherever there is genuine faith, whenever the Torah is written on the heart, there the “new covenant” is active.

Finally, the “old covenant” does not describe the life of God’s people before the coming of Messiah. It is a term coined by Paul to describe faithlessness—the very thing that defined the nation of Israel when she fell into idolatry, worshipping the Golden Calf. The “old covenant” is Paul’s term for living with the knowledge of Torah but not receiving it by faith, and therefore missing the very goal of the Torah, Who is Yeshua. Paul’s “old covenant” is reading the Tanach with a veil over it so that the glory of Yeshua cannot be seen. The “old covenant” is the Torah without faith. And when the Torah is accepted apart from faith it comes as a letter of condemnation and death, not the life-giving tree God intends for His elect ones.

A second misunderstanding is that the minutiae of the Torah are now summed up in two, simple statements: loving God and loving one’s neighbor. The misunderstanding comes from two directions: 1) not understanding why the Torah was summed up this way, and 2) not understanding what is meant by “love.”

The habit of the Sages to distill the Torah into its irreducible minimums is well known. That “loving God” and “loving neighbor” became a predominant summation must be accredited to the fact that the Ten Words (usually called the Ten Commandments) can be nicely divided along these lines: the first half being Godward, and the last half being manward.

But why did the Sages seek to distill the Torah into a few statements? It was not to reduce the “minutiae,” but to help direct the people toward a proper motivation for performing the mitzvot (commandments). Constantly, in the rabbinic writings, halachah (the determination of what should be done) is matched with aggadah (a story describing the motivation for doing what should be done). The Sages understood that the mere doing of the mitzvot, while good in one sense, was not complete unless one’s motivation was also right. To cast the mitzvot as “loving God” and “loving one’s neighbor” helped keep a proper focus for why one was doing the mitzvot in the first place. So summing up the Torah this way was never conceived as a method to replace it, but as a way to encourage proper motivation for doing it.

That Yeshua was not the first to sum up the mitzvot in the dual “love God” and “love your neighbor” is well known. Others before Him had said the same things, and given other summations as well. So Yeshua, rather than giving something unique or novel by saying that the whole Torah is summed up in “loving God” and “loving one’s neighbor,” was simply agreeing with a well-known teaching of His day.

Furthermore, to understand “love God” and “love your neighbor” as reducing the minutiae of the Torah is to misunderstand the biblical concept of “love.”

“Love” in the Scriptures is a covenant term, as seen by the fact that “love” was used even in non-biblical covenants of the Ancient Near East in this same way. The word “love” found in covenant contexts means “to act faithfully toward the one with whom a covenant has been made.” Thus, to “love” someone within the context of covenant relationship means to be loyal and faithful to that person as the covenant demands.

Likewise, the majority of times the word “love” is found in the Tanach in which the focus is loving God or God loving His people, it is clearly linked in the context to obedience/loyalty to the covenant. Here are a few examples:

Deut. 7:8 but because the LORD loved you and kept the oath which He swore to your forefathers,

Deut. 10:12 “Now, Israel, what does the LORD your God require from you, but to fear the LORD your God, to walk in all His ways and love Him, and to serve the LORD your God with all your heart and with all your soul,

Deut. 11:13 “It shall come about, if you listen obediently to my commandments which I am commanding you today, to love the LORD your God and to serve Him with all your heart and all your soul,

Deut. 13:3 you shall not listen to the words of that prophet or that dreamer of dreams; for the LORD your God is testing you to find out if you love the LORD your God with all your heart and with all your soul.

Is. 56:6 “Also the foreigners who join themselves to the LORD, To minister to Him, and to love the name of the LORD, To be His servants, every one who keeps from profaning the Sabbath And holds fast My covenant;

Psa. 31:23 O love the LORD, all you His godly ones! The LORD preserves the faithful And fully recompenses the proud doer.

Therefore, if one accepts this use of “love” in the Scriptures, then loving God and loving one’s neighbor means “acting in accordance with the covenant in which we both live.” How does one act in accordance with the covenant? The covenant that God has made with us, and which we enter by faith in Yeshua, is one which contains commandments. We show our faithfulness to the covenant by keeping these commandments. We do not keep the commandments to get into the covenant; we keep the commandments precisely because we are members of the covenant. Obedience to God is the hallmark of our covenant membership, or to say it another way, “loving God” is the mark of true covenant members.

If one accepts this definition of “love,” then the “minutiae” of the covenant, rather than being a burden, becomes the opportunity to “know” God at every level of one’s life, and in every activity (1Corinthians 10:31 “Whether, then, you eat or drink or whatever you do, do all to the glory of God”). Even as a man and wife who genuinely love each other desire to know even the details of each others likes and dislikes, so our love of God drives us to know the “minutiae” of what He, in His infinite holiness, desires and what He despises.

Furthermore, the question that must be asked at this point is whether or not the Torah is deemed to be “holy.” (Romans 7:12 “So then, the Torah is holy, and the commandment is holy and righteous and good.”) If the Torah is holy, than it means that as it was given, even the “minutiae” is holy and good. At what point did it cease being “holy and good?” Apparently Yeshua considered even the smallest part of the Torah to be important, because He speaks of it in these terms (Matthew 5:17ff).

Therefore, the summing of the commandments under the rubric of “love God” and “love your neighbor” was not given to show that Yeshua’s teaching superseded or in someway “trumped” the Torah. It was rather gathering the Torah principles into two, easily remembered principles which would help define the proper motivation for doing Torah, all of it.

One further thought on this issue: the idea that the “New Testament” portrays a higher ethic than the “Old Testament” is ill-founded. To suggest that the annihilation of Israel’s enemies somehow puts Israel as less spiritual than the followers of Yeshua who are commanded to “love your enemies” is to misunderstand both texts. First, it was at God’s direction that Israel engaged in battle to annihilate their enemies. When they spared some, God was the one pointing out their disobedience. So if Israel’s activities in her war against the inhabitants of the Land are viewed as a diminished ethic, then the charge must be laid at God’s door, not Israel’s. They were only doing what God had instructed them to do. And is not this the goal of true spirituality—doing what God says to do?

Secondly, Yeshua’s command to “love your enemy” must be understood to exist within the context of community. He is not telling His disciples to “love Rome” or to somehow “deal kindly with paganism.” If He were, then He surely contradicts Himself when He tells His disciples to take up swords with them as they went out to do their work (Luke 22:36), even indicating that a sword was more important than a coat! No, His exhortation to “love one’s enemy” describes someone close enough to insult you (slap on the face). This is the one within your community with whom you have grave disagreements, who may even engage in evil speech about you. It is this enemy you must love, pray for, and for whose sake you must do good. Neither the Father nor the Son ever requires His people to act benevolently toward those whose goal is to be Satan’s tool of destruction. The same God who charged the ancient Israelites with the task of wiping out the pagan nations in the Land is the God who sends the terrors of the Great Tribulation upon the earth, with devastating effect. And, the hand that holds the keys to the Lake of Fire is a hand pierced through for our sins. The love of God does not negate His justice, and all of His enemies will perish.

The idea that the words of Yeshua in Matthew 11:11-13 teach some kind of demarcation between “old” and “new” is a misreading of the text.

Truly I say to you, among those born of women there has not arisen anyone greater than John the Baptist! Yet the one who is least in the kingdom of heaven is greater than he. From the days of John the Baptist until now the kingdom of heaven suffers violence, and violent men take it by force. For all the prophets and the Law prophesied until John.

First, the section is lifted out of the context. Verse fourteen (at least) is needed to complete the idea, for it is attached by means of the word “and”: “And if you are willing to accept it, John himself is Elijah who was to come.”

The first thing to note is the meaning of the word “until” in the Scriptures. The Hebrew עַד, ‘ad, means “up to this point,” “until,” “reaching to this point,” etc. It thus may carry the sense of “movement to a goal” or “movement toward a fixed point.” Consider Psalm 110:1, “Sit at my right hand until I make your enemies a footstool for your feet.” What this phrase means is that the sitting occurs with a result that the enemies are made a footstool. What it does not mean is that He sits until the enemies become a footstool, and then He no longer sits. For “sitting at the right hand” is the picture of reigning on His throne. He does not cease reigning (sitting) when His enemies are subdued. Rather, He sits (reigns) with a view to the subjugation of His enemies.

Another example is Genesis 43:25 “So they prepared the present for (literally “until”) Joseph’s coming at noon; for they had heard that they were to eat a meal there.” They prepared a present until Joseph’s coming at noon. Does that mean they prepared a gift until Joseph came and then they ceased preparing the gift? No. It means they prepared a gift with a view to Joseph’s coming at noon.

Now this is the manner in which “until” is used in Matthew 11:13, “For all the prophets and the Torah prophesied with a view to John.” But this is meaningless unless the next phrase is added: “And if you are willing to accept it, John himself is Elijah who was to come.” The point is now obvious: the Torah and the Prophets all prophesied with a view to the coming of Messiah Who would be preceded by Elijah. Yeshua is simply saying that in many of the prophets the coming of Elijah was at the very end, before the “great and terrible Day of the Lord,” but that John functioned in the “spirit of Elijah,” himself coming before Yeshua as the suffering Servant of the Lord. The prophets not only spoke of Yeshua’s final reign, they also spoke of His suffering. Elijah would precede His coming as the victorious Messiah, but John would herald His coming as the Lamb of God. In the context, Yeshua wishes to focus attention on what the prophets were saying about His first appearance.

The point therefore is that John was, in some measure, the focal point of the prophetic promise of Messiah in His servant role, since he functioned as the forerunner of the Messiah in His first advent. It would be disastrous to claim that all of the prophetic Scriptures were in every way fulfilled and thus exhausted by the time of Yeshua’s first coming! This is not what Yeshua means here. Rather, His point is that all of the prophets spoke of Him, and of this time in history when redemption would be finalized through His death, resurrection, ascension, and heavenly intercession, all of which is necessary for His eventual and final return to reign in the Millennial Kingdom.

But the clear and undisputed fact that Yeshua was and is the goal of the Torah does not necessitate a heightened spirituality in the era of the incarnation. The point simply is that all true spirituality is connected to and finds its fulfillment in Yeshua and the Spirit Who works in complete harmony with Him. If the righteous one of ancient Israel looked forward with anticipating faith to the Messiah Yeshua, and we, in our modern day, look back to His earthly appearance, and find in Him the object of our saving faith, then both the ancient and the modern stand on the same platform, at the same “height.” The one spirituality does not outdo the other.

One of the primary issues fostering the idea that spirituality increased after the coming of Yeshua is the matter of the Spirit’s work. It is usually argued that the increased activity of the Spirit in the Apostolic era proves this to be the case. There is not doubt that the activity of the Spirit in the Apostolic era is a significant signal that the last days had arrived, and the promised work of the Spirit was therefore being realized. If by nothing else, the mere increase of the mention of the Spirit shows this to be the case.

But we must ask ourselves some very fundamental questions. 1) was the method of salvation different before and after the coming of Yeshua? (This traces the question of whether or not the increased work of the Spirit was specifically in the realm of producing a greater holiness.) 2) Is the increased activity of the Spirit in the Apostolic era related to a specific mission? 3) Does the increased activity of the Spirit in the Apostolic era produce a more significant level of spirituality within the people of God?

While the evangelical Christian church would deny that there have existed two “methods” of salvation, in practical terms Christianity has taught this. Or to put it another way, the Church’s creeds and theology affirm the singular nature of salvation, but the practice of the Church tells another story.

Of course, some of the Christian church (and an increasing number in our day, it seems) readily admit that there were two ways of salvation: one for those before Messiah, and one for those after Him. Some might even say that the line of demarcation was not so much the death and resurrection of Messiah, but His appearance upon the earth (so that John the Baptist becomes a kind of “line of demarcation”).

Avoiding a “straw man argument,” I still maintain that it is a disaster theologically to postulate a “two-ways of salvation” theory. For if that were the case, then some were “saved” apart from the death of Yeshua, and this can in no way be sustained by either the Tanach nor the Apostolic Scriptures. To the complete contrary, all of the Apostolic writers affirm that salvation is only by faith in Yeshua, even for those who lived before His appearance. As I have noted above, the two classic examples as far as the Apostle Paul is concerned are Abraham and David. Paul’s argument in Romans 4 is fundamentally flawed if, while using Abraham and David as examples of justification by faith, they were, in fact, justified on grounds other than faith in Yeshua. The very fact that Paul uses Abraham and David as prime examples of what he is teaching about justification by faith illustrates his presupposition, namely, that all are justified on the same grounds, by the same exercise of faith in the same object, Yeshua.

But we should ask further what Paul believed about God’s method of justification. What takes place when a sinner is justified? Even a cursory look at Paul’s teaching in this area reveals that he links the activity of the Spirit in regeneration (making the soul alive to see, understand, and receive the gospel) as an integral and necessary part of justification. That being the case, he must have believed that the same Spirit did the same work of regeneration in the lives of the ancient believers as well as in those of his day. This conclusion is inescapable.

• Circumcision of the heart is accomplished by the Spirit, Rom 2:29, but the Torah exhorted the people of Moses’ day to have their hearts circumcised, cf. Deut. 10:16; 30:6. Jeremiah exhorted the people to the same action, Jer. 4:4

• Apart from the Spirit, Yeshua is veiled in the Torah, 2Cor 3. If those redeemed in ancient times were saved as we are, i.e., by faith in Yeshua, they did so only as the Spirit unveiled Him in the Tanach, opened their eyes to see Him, and gave them faith to believe.

• Apart from the Spirit, the Torah only brings condemnation, damnation, and death, 2Cor 3; Rom 8:2; Rom 8:9ff. How then could David write that the Torah restores the soul unless the Spirit was active in this restoration? Psalm 19:7ff

• The requirements of the Torah can only be lived out by those who have the Spirit, Rom 8:9ff. Those who do not have the Spirit cannot keep the Torah. Since it is clear that those who were of true faith in ancient Israel were described as obeying Torah, we must conclude they had the Spirit.

• The deeds of the flesh can only be put to death by the Spirit, Rom 8:13. Did the believers in ancient Israel put to death the deeds of the flesh? If not, how could they have obtained any personal holiness?

• Knowledge that one is truly a child of God is given by the Spirit, Rom 8:16. Did the believers of old know they were God’s children? Surely the did, for they are put forward as models of holiness for us to follow (Noah, 2Peter 2:4; Elijah, James 5:17; Abraham, Romans 4:16, 19; Sarah, 1Peter 3:6; and all those listed in Hebrews 11).

• The Spirit helps us in our prayers, taking our requests before God, Rom 8:26. Were the believers of old helped in their prayers? If not, were their prayers effective? By all accounts they were (note the prayer of Elijah, James 5:17). This presupposes the presence of the Spirit aiding them in their prayers.

• No one can know the thoughts of God apart from the Spirit’s work of revelation/illumination, 1Cor 2:10ff. Did the believers of old know the thoughts of God? Surely they did, as the Tanach everywhere attests.

• Sanctification is the work of the Spirit of God, 1Cor 6:11, and it is only in the Spirit that one is able to overcome the flesh, Gal 5:16. Were the believers of old being sanctified? Were they able to overcome the flesh?

• Eternal life is connected with the righteousness produced by the Spirit, Gal 6:8. Did the believers of old possess eternal life?

• Salvation is possible only through the washing of regeneration and the renewing of the Holy Spirit, Tit 3:5. Did the believers of old possess salvation?

From these passages it is eminently clear that at least Paul’s working presupposition was that the faith of all believers, in all eras, was directly tied to the work of the Spirit of God in connection with the salvific plan of the Father, based upon the work of Yeshua as Prophet, Priest, and King.

The increased activity of the Spirit in the Apostolic Era was an increase in quantity, not quality. If we stop for a minute and ask those who believe the Spirit’s work in the Apostolic era was an increase in quality—if we ask what they actually mean by this, their answers betray the underlying notion that there are two ways of salvation. For if the work of the Spirit is greater in quality (= better, producing more holiness), then does this mean that the believers in and following the time of Yeshua were more holy? Would this mean that they have a closer relationship with God or in some measure knew Him in a way the ancient believer did not? To postulate such an outcome is to admit that our salvation experience is greater than theirs, for salvation consists not merely in forgiveness of sins but ultimately in sanctification and communion with God. If the believers in and following the time of Yeshua have the opportunity for a level of holiness not given to the believers of former generations, then there are two standards of holiness, and consequently two kinds of salvation. But the standard of holiness maintained both by the Torah (Lev 11:44) as well as by the Apostles (1Pet 1:16) is nothing less than the holiness of God Himself. It is to this standard that He calls His people in every era, not being satisfied by a lower standard in the time before the Messiah, and expecting a higher one after His appearance. In fact, the standard of holiness He requires is nothing short of the highest standard, i.e., the standard of His own holiness, “be holy as I am holy.” And the Torah is a verbal revelation of His holiness.

The increased mention of the Spirit of God in the Apostolic Scriptures coincides with the fulfillment of the promise made by the prophets that in the last days the Spirit would be poured out afresh upon Israel to enable her to be a light to the nations. This means that the Spirit would be increasingly active among the Gentiles as the promised harvest of the nations is realized. That the majority of the Apostolic Scriptures were from the hand of Paul, himself the Apostle to Gentiles, gives yet another reason why the work of the Spirit in the Apostolic era is so much more noted than in the Tanach. In ancient Israel, the Spirit of God is virtually inactive among the nations. In contrast, in the Apostolic Writings, dominated by the Pauline epistles, the promised activity of the Spirit among the Gentiles becomes a major focus. Paul wanted his readers to recognize the fact that the promised ingathering of the nations, begun at Shavuot (Acts 2) was surely in progress, and that God had appointed him to be a major leader in that endeavor. The promised enablement of the Spirit makes possible the ingathering of the nations.

The obvious answer to this is “no.” The activity of the Spirit is wider, upon a greater number of people, and therefore more prominent, but this increase is in quantity, not quality. The same Spirit is active with the same message, producing faith in the same Object (Yeshua), and sanctifying God’s children according to the same level of holiness in all eras and all generations. To conclude otherwise is to ignore the overarching teaching of the Scriptures.

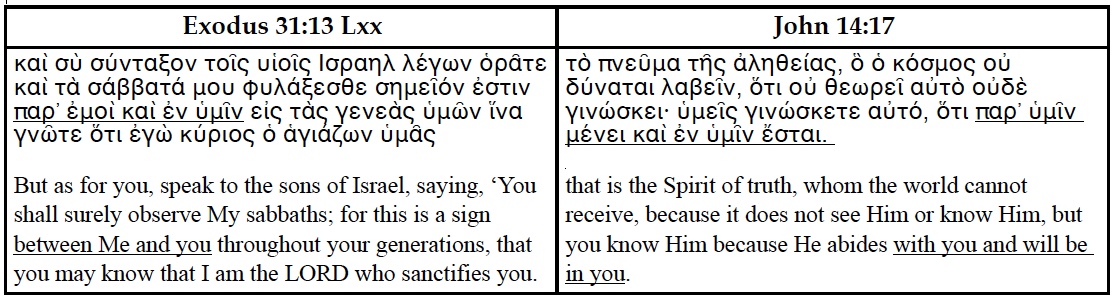

But if this be the case, how is one to understand a verse like John 14:17—

that is the Spirit of truth, whom the world cannot receive, because it does not see Him or know Him, but you know Him because He abides with you and will be in you.

Usually this verse is brought forward by those who see a new and enhanced spirituality in the Apostolic era as teaching that the Spirit was only “with” the believers of ancient times (“with” = less intimate) while He is “in” the believers following the ascension of Yeshua (“in” = more intimate). But this is a naive approach to the use of prepositions in the Greek. “With you” utilizes the preposition πάρα, “with, alongside of” while “in you” has ἐν, usually translated “in, by,” etc. But what language was Yeshua speaking? Most likely He was speaking Hebrew, maybe Aramaic. What do the Greek prepositions in the text at hand reveal about what words Yeshua might have used in this famous saying?

Interestingly, the very common text of Exodus 31:13 uses almost the same construction in the Lxx Greek:

Here, in Exodus 31:13, the same Greek construction as in John 14:17 is used to translate the common Hebrew בֵּיןְ… וּבֵין, “between . . . between.” It could be that the phrase “with you . . . will be in you” simply reflects the Semitic construction “between you,” meaning that the Spirit would be active among them as He had been while they walked with Yeshua. Yeshua’s point would thus be that even after He left, the Spirit’s work would remain, strengthening them, leading them, and equipping them to accomplish the work He had commissioned them to do.

If the Greek construction does not reflect a Hebrew use of the preposition בֵּין, “between,” “among,” the Greek could just as easily be understood as “with you (now) … will be among you (in the future).” Whatever the case, the idea that the Spirit of God is somehow localized “beside” you now but “indwelling” you later cannot be sustained on the basis of the prepositions—they are far too fluid in their meaning to allow such strict delineation.

It should also be noted that there are significant textual variations on this verse in the Greek text. The UBS text gives the reading “with you … will be in you” its lowest rating of probability for being the original text. In fact, Westcott in his commentary opts for the reading that yields “He abideth by you and is in you” (taking the present tense as the original reading, not the future tense).1 Whatever the case, this verse should surely not be considered foundational for the belief that there was an increased, personal and internalized work of the Spirit after the death and resurrection of Yeshua.

Another verse often pointed to by those who believe the time following Yeshua brought a higher spirituality to the people of God is John 7:39:

But this He spoke of the Spirit, whom those who believed in Him were to receive; for the Spirit was not yet given, because Yeshua was not yet glorified.

The first thing that we should note about this text is that the word “given” in the translation above is added by the translators. Though it shows up in some manuscripts, the clear weight of the early Greek manuscripts do not include it. Its addition in some of the manuscripts is best explained as an attempt to assure the reader that John was not denying the existence of the Holy Spirit.

What could John mean by stating that “the Spirit was not yet?” The key is in the following phrase, “because Yeshua was not yet glorified.” That is, until Yeshua ascended to the Father, reclaiming the glory He had set aside for His work as the Servant Messiah (cf. John 17:5), the Spirit could not become active in the task of harvesting the nations. The phrase “the Spirit was not yet” must mean, therefore, that the work of ingathering the nations, requiring the intercession of Yeshua as the High Priest in the heavenly Tabernacle (cf. Hebrews 7-9), could not be accomplished until Yeshua ascended as High Priest and the Spirit enabled the disciples to launch the final harvest of the nations through the message of the gospel they would carry.

It seems quite clear that John was referring to the special and specific work of the Spirit in equipping the disciples to be the initiating force in the promised harvest of the nations. This is why they were to wait in Jerusalem until the Spirit would empower them for their mission:

but you will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you shall be My witnesses both in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and even to the remotest part of the earth. (Acts 1:8)

Thus John’s statement that “the Spirit was not yet” must be interpreted to mean that He was not yet active in the harvest work of the nations, a work He would activate after the ascension of the risen Messiah. Surely the verse cannot be interpreted to mean that the eternal Spirit was not yet in existence, or that somehow the Spirit of God was inactive. Any reading of the Hebrew Scriptures shows this to be entirely out of the question.

Once again, this verse, like others brought forward, when taken in its context, in no way supports the idea that a higher spirituality was initiated during and after the time of Yeshua.

Conclusion

It seems clear, then, that the idea of a greater spirituality among the people of God after the appearance of Yeshua is not warranted. It is disproved:

1) by the fact that the Scriptures everywhere speak of only one means of salvation for all people, in all generations;

2) that the Spirit must be active in all phases of personal salvation, from justification through sanctification, leading to glorification;

3) that the increased mention of the Spirit in the Apostolic Scriptures reflects the new work of the Spirit among the Gentiles, and the equipping of the Jewish believers, particularly the disciples of Yeshua, to effect this ingathering of the Gentiles.

Tim Hegg

President / Instructor

Tim graduated from Cedarville University in 1973 with a Bachelor’s Degree in Music and Bible, with a minor in Philosophy. He entered Northwest Baptist Seminary (Tacoma, WA) in 1973, completing his M.Div. (summa cum laude) in 1976. He completed his Th.M. (summa cum laude) in 1978, also from NWBS. His Master’s Thesis was titled: “The Abrahamic Covenant and the Covenant of Grant in the Ancient Near East”. Tim taught Biblical Hebrew and Hebrew Exegesis for three years as an adjunct faculty member at Corban University School of Ministry when the school was located in Tacoma. Corban University School of Ministry is now in Salem, OR. Tim is a member of the Evangelical Theological Society and the Society of Biblical Literature, and has contributed papers at the annual meetings of both societies. Since 1990, Tim has served as one of the Overseers at Beit Hallel in Tacoma, WA. He and his wife, Paulette, have four children, nine grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren.