Articles

Leviticus 23 contains a list of the appointed times of the Lord with some instructions on the observance of each. The first of these appointed times is the Sabbath, which is the only weekly convocation (Lev 23:3). The rest of the chapter lays out the annual appointed times that can be divided in two groups, Spring and Fall appointed times.

The Spring Appointed Times:

The Fall Appointed Times:

In the text, all of these appointed times are assigned a specific date, except for one–the Feast of Weeks.

The Feast of Weeks is connected to Passover and the Feast of Unleavened Bread by a fifty-day (Lev 23:16), or seven-week period (Num 16:9) known as The Omer.1

The start of The Omer is the debated issue that will be explored in this paper. The goal is to identify “the sabbath” in the phrase “the day after the sabbath” (Lev 23:11, 15) which is the day that The Omer begins. While this seems like an easy conclusion to reach, within Messianic, Pro-Torah circles there are two prominent views in understanding what is meant by “the sabbath” and both of these views can be supported by Scripture. This is an important debate because The Omer determines when individuals, families, and communities will observe the Feast of Weeks, an appointed time of the Lord.

The Sadducean Method: The Omer begins on the day after the weekly Sabbath that falls within the seven-day Feast of Unleavened Bread.

In this reckoning, the day on which the barley sheaf is waved will always fall on a Sunday and therefore, the Feast of Weeks will also be on a Sunday. This reckoning is referred to by some as the “Biblical Method” because through a simple reading of the Text, this seems to make the most sense.

The Pharisaic Method: The Omer begins on the day after the first day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread which is a day of “no laborious work.”

In this reckoning, the day on which the barley sheaf is waved could fall on any day of the week within the seven days of Unleavened Bread and it could be a different day each year. This reckoning is referred to by some as the Rabbinic Method because this is how Rabbinic Jews reckon the day on which the barley sheaf is waved and the omer count begins.

Despite the differences, these two views do agree on certain key areas of understanding The Omer. The first is the context of the passage–the Feast of Unleavened Bread. It is clear that the phrase “the day after the sabbath” is referencing two days that fall within the seven days of Unleavened Bread, 1) “the sabbath” and 2) “the day after the sabbath.” Again, the identity of these two days is the question that needs to be answered.

A second area of agreement is in understanding the phrases “seven complete sabbaths” (Lev 23:15) and “seventh sabbath” (Lev 23:16). Both methods understand these phrases as a reference to seven, seven-day weeks and not seven literal Sabbath days.

In the following explanations for each method, these areas of agreement are presented in support of their respective conclusions.

Please note that this paper is not a scholarly dissertation nor is it exhaustive. The author’s intent is for this information to serve as a springboard for the reader to do research in this area in order to become more familiar with this topic and decide for themselves which method to follow.

5 In the first month, on the fourteenth day of the month at twilight is the Lord’s Passover. 6 Then on the fifteenth day of the same month there is the Feast of Unleavened Bread to the Lord; for seven days you shall eat unleavened bread. 7 On the first day you shall have a holy convocation; you shall not do any laborious work. But for seven days you shall present an offering by fire to the Lord. On the seventh day is a holy convocation; you shall not do any laborious work.’” – Lev 23:5-8

Leviticus 23:5 prescribes the date and time for sacrificing and then eating the Passover sacrifice (Exod 12:6; Deut 16:4, 6).

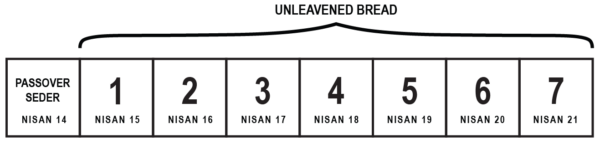

Leviticus 23:6-8 describes the Feast of Unleavened Bread, a seven-day festival that takes place over a span of specific dates, Nisan 15-21 (Exod 13:6-7, 23:15, 34:18; Num 28:17; Deut 16:3, 8), however, specific days of the week are not assigned to these dates (Figure 1). This means that, as an annual appointed time, Unleavened Bread may start on the first day of the week in one year and on the third day of the week the following year. The day of the week that Unleavened Bread begins and ends is not important, but the dates are.

9 Then the Lord spoke to Moses, saying, 10 “Speak to the sons of Israel and say to them, ‘When you enter the land which I am going to give to you and reap its harvest, then you shall bring in the sheaf of the first fruits of your harvest to the priest. 11 He shall wave the sheaf before the Lord for you to be accepted; on the day after the sabbath the priest shall wave it. – Lev 23:9-14

In Leviticus 23:9-14, the Lord instructs Moses about the “first fruits” of the land (v. 10), namely the barley harvest. A sheaf (omer) of barley is to be brought into the temple, by the priest, and offered up to the Lord. This event is supposed to take place on “the day after the sabbath” (v. 11).

The context of Leviticus 23:11 is the Feast of Unleavened Bread and therefore, the sabbath mentioned is the weekly Sabbath that falls within the seven-day festival. The day after the weekly Sabbath, the first day of the week, is the day that the sheaf is waved. This is determined by looking at the Hebrew of the phrase “the day after the sabbath” where “the sabbath” is הַשַּׁבָּ֔ת, HaShabbat, a designation in Scripture given only to the weekly Sabbath and never a festival day.

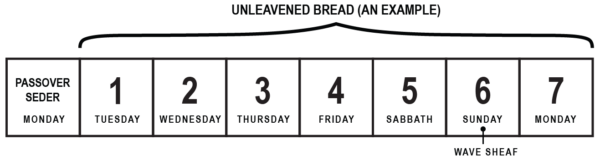

Because Unleavened Bread can begin on any day of the week, the weekly Sabbath that falls within these seven days will move around within the seven dates from year to year (Figure 2). Once the first day of the first month is determined, then the dates for the Spring appointed times can be established and the day to wave the barley sheaf is assigned.

15 ‘You shall also count for yourselves from the day after the sabbath, from the day when you brought in the sheaf of the wave offering; there shall be seven complete sabbaths. 16 You shall count fifty days to the day after the seventh sabbath; then you shall present a new grain offering to the Lord. – Lev 23:15-16

Leviticus 23:15-21 makes it clear that on this same “day after the sabbath”, the counting of the days leading up to the Feast of Weeks begins. That is, fifty days, to the day after the “seventh sabbath”, there are to be “seven complete sabbaths”. Here we have two more phrases that deserve some attention: “seventh sabbath” and “seven complete sabbaths.”

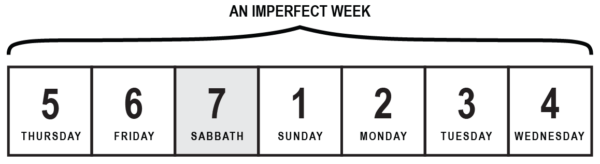

The plain reading of “seventh sabbath” can be understood as the last of seven consecutive weekly Sabbaths. But how is the phrase “seven complete sabbaths” to be understood? If the “seven sabbaths” are to be complete, what does an incomplete Sabbath look like?

In this usage of “sabbath” we find another meaning for this word. This time it refers to a week or a group of seven days and not the weekly Sabbath. This same usage is found in the instructions for counting the Jubilee year where a “sabbath of years” is considered to be a group of seven years or a week of years.

You are also to count off seven sabbaths of years for yourself, seven times seven years, so that you have the time of the seven sabbaths of years, namely, forty-nine years. – Lev 25:8

Furthermore, the Feast of Weeks is the literal English translation of the Hebrew, חַ֤ג שָׁבֻעוֹת֙, Chag Shavuot. While Leviticus 23 does not designate the fiftieth day as the Feast of Weeks, this name is used elsewhere in Scripture:

“You shall celebrate the Feast of Weeks, that is, the first fruits of the wheat harvest…” – Exod 34:22

“Also on the day of the first fruits, when you present a new grain offering to the Lord in your Feast of Weeks, you shall have a holy convocation; you shall do no laborious work.” – Num 28:26

“Then you shall celebrate the Feast of Weeks to the Lord your God with a tribute of a freewill offering of your hand, which you shall give just as the Lord your God blesses you;” – Deut 16:10

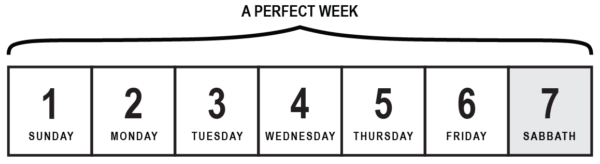

Just as the Jubilee year is a week of years, the Feast of Weeks is a week of weeks. This is why it was important for there to be seven complete, or full, weeks of seven days because the goal was to reach the fiftieth day.

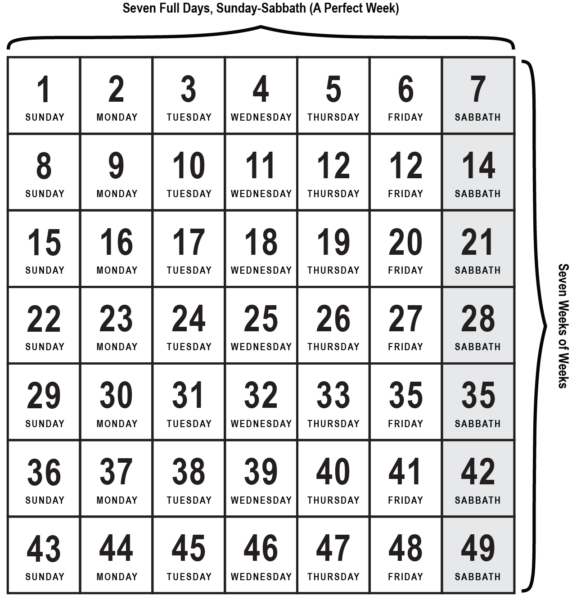

A “complete sabbath” could also indicate a week that, in addition to having seven full days, it starts with the first day of the week and ends with the seventh day, the weekly Sabbath2 ( Figure 3). In Genesis, the week of creation, the archetype of all weeks, began with the first day and ended on the Sabbath. The week of creation is a Biblical example of a complete or perfect week.

It should be noted that Unleavened Bread is also a seven-day period but it is not referred to as a week. This could be because this seven-day period will not always be a complete or perfect week, i.e., it will not always start on the first day of the week and end on the weekly Sabbath.

The “day after the sabbath”, the day that barley sheaf is waved, and the Feast of Weeks are not assigned specific dates in Leviticus 23 because the date that they occur will be different year after year.

The day on which The Omer begins cannot be determined until the beginning of the first month is identified and the dates for Passover and the seven days of Unleavened Bread are established. The day on which the Feast of Weeks is celebrated is identified once the day to begin The Omer is assigned.

The day on which The Omer begins will always be a Sunday, the first day of the week, which is the “day after the sabbath.” If we then count seven complete weeks, the following day, the Feast of Weeks, will also fall on a Sunday. Hence the Christian tradition of Pentecost Sunday which is fifty days after Easter Sunday. Pentecost is the Greek name for the Feast of Weeks. Pentecost means fiftieth, i.e. the 50th day.

Finally, if the Sabbatical Year is patterned after a week of seven days, from the first day of the week to the seventh day, then the Year of Jubilee, the 50th year, is patterned after the Feast of Weeks, the 50th day (Figure 4).

9 Then the Lord spoke to Moses, saying, 10 “Speak to the sons of Israel and say to them, ‘When you enter the land which I am going to give to you and reap its harvest, then you shall bring in the sheaf of the first fruits of your harvest to the priest. 11 He shall wave the sheaf before the Lord for you to be accepted; on the day after the sabbath the priest shall wave it. – Lev 23:9-11

15 You shall also count for yourselves from the day after the sabbath, from the day when you brought in the sheaf of the wave offering; there shall be seven complete sabbaths. 16 You shall count fifty days to the day after the seventh sabbath; then you shall present a new grain offering to the Lord. – Lev 23:15-16

According to these passages in Leviticus 23, from “the day after the sabbath” there are to be seven “complete sabbaths,” or forty nine days, and on the day after the “seventh sabbath,” the fiftieth day, is the Feast of Weeks. In the phrases “seventh sabbath” and “seven complete sabbaths,” the word “sabbath” is not a reference to the weekly sabbath, but rather, to a week–a group of seven days.

The Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Tanach dating back to the 3rd century, translates Leviticus 23:15-16 like this:

15 And ye shall number to yourselves from the day after the sabbath, from the day on which ye shall offer the sheaf of the heave-offering, seven full weeks:

16 until the morrow after the last week ye shall number fifty days, and shall bring a new meat-offering to the Lord.3

The Greek text agrees with the suggested translation that “seventh sabbath” and “seven complete sabbaths,” are understood to be “seven weeks” and not “seven weekly Sabbath days”.

Deuteronomy 16 also supports the view that this was a seven week period:

9 “You shall count seven weeks for yourself; you shall begin to count seven weeks from the time you begin to put the sickle to the standing grain. 10 Then you shall celebrate the Feast of Weeks to the Lord your God… – Deut 16:9-10

In this passage the word sabbath (שַׁבָּ֥ת, shabbat) is not used to indicate a week. Instead, the word for week, shavua (sg.; שָׁבֻעֽוֹת, shavuot pl.), is used. Hence the name Feast of Weeks, or חַ֤ג שָׁבֻעוֹת֙, Chag Shavuot, a reference to the seven-week period leading up to this appointed time.

In Leviticus 25 the word “sabbaths,” (שַׁבְּתֹ֣ת, shabbatot), is also used to designate a week, i.e. a group of seven.

“You are also to count off seven sabbaths of years for yourself, seven times seven years, so that you have the time of the seven sabbaths of years, namely, forty-nine years.” – Leviticus 25:8

The Jubilee is the fiftieth year that comes after “seven sabbaths of years”. In other words, seven groups of seven years. This passage demonstrates that the word “sabbath” does not always refer to the weekly convocation. It is the context of the passage that gives the word its meaning.

The key to determining which day The Omer count begins is identifying “the sabbath” in the phrase “the day after the sabbath” in Leviticus 23:11, 15. These passages should be read in light of Leviticus 23:6-8, the seven days of the Feast of Unleavened Bread. Which one of these seven days is “the sabbath”?

The Sadducean Method has determined that the “sabbath” in question is the weekly Sabbath day that falls during the seven days of Unleavened Bread. The proponents of the Pharisaic Method, on the other hand, understand the “sabbath” to be the first day of Unleavened Bread. Just as the weekly Sabbath is a day of physical rest and a cessation of work related activity,4 the appointed times are also given the same restriction of “no laborious work.” While the festival days are not given the designation of “sabbath” in the Tanach,5“no laborious work” can also imply rest.

This view is supported by the very first Passover that took place in the Land under the leadership of Joshua.

10 While the sons of Israel camped at Gilgal they observed the Passover on the evening of the fourteenth day of the month on the desert plains of Jericho. 11 On the day after the Passover, on that very day, they ate some of the produce of the land, unleavened cakes and parched grain. – Josh 5:10-11

Once Israel entered the Land after crossing the Jordan, and only after all of the men had been circumcised, they observed Passover at Gilgal. In Leviticus 23:14 Israel is commanded not to eat of the produce until the first barley sheaf has been offered and accepted. In Joshua 5 it says that “on the day after the Passover, on that very day, they ate some of the produce of the land.” It stands to reason that “the day after the Passover” was the day that Joshua, Eleazar the High Priest and all of Israel recognized as the day to “wave the sheaf” and begin the count of seven weeks, or forty nine days, to the Feast of Weeks.6

However, this passage raises yet another question. Passover is not a day, it is an ordinance (Exod 12:24), it is a meal (Exod 12:8-11), and more specifically, it is a sacrifice (Exod 12:27). So how are we to understand “Passover” in this verse?

The word “Passover,” like the word “sabbath”, is another word in Scripture with multiple meanings and where the context of the passage determines the meaning. In Ezekiel, “Passover” is used to reference both the Passover meal and the Feast of Unleavened Bread.

In the first month, on the fourteenth day of the month, you shall have the Passover, a feast of seven days; unleavened bread shall be eaten. – Ezek 45:21

Because they are connected, over time these two observances have become synonymous and are called by the name of the more prominent event, Passover. This convention has been passed down to our present time. It is not uncommon for the seven days of Unleavened Bread to be referred to as the seven days of Passover.

In Joshua 5, “Passover” is a reference to the first day of Unleavened Bread; a day on which there was a holy convocation and no laborious work was allowed (Lev 23:6-8). It is understood that every year the Passover Seder, which starts in the evening on Nisan 14th, will inevitably overlap into Nisan 15th, the first day of Unleavened Bread, making an inextricable connection. The connection of the two is indicated in the Apostolic Scriptures.

Now the Passover and Unleavened Bread were two days away… – Mark 14:1

On the first day of Unleavened Bread, when the Passover lamb was being sacrificed, His disciples said to Him, “Where do You want us to go and prepare for You to eat the Passover?” – Mark 14:12

Now the Feast of Unleavened Bread, which is called the Passover, was approaching. – Luke 22:1

Then came the first day of Unleavened Bread on which the Passover lamb had to be sacrificed. – Luke 22:7

If “Passover” in the phrase “the day after Passover” is the first day of Unleavened Bread, Nisan 15th, then “the day after Passover,” the day on which the barley sheaf was waved and The Omer count began, is Nisan 16th.

This interpretation finds support in the following Biblical and Historical witnesses.

11 and he shall lift up the sheaf before the Lord, to be accepted for you. On the morrow of the first day the priest shall lift it up. – Leviticus 23:117

The early translators of the Hebrew Text into Greek understood the barley sheaf was to be waved on the day after ‘the first day’ of Unleavened Bread.

The Targums (Targumim) are 1st century translations, explanations or paraphrases of the Torah from Hebrew to Aramaic, the common language of the time. The Targums are useful today to help modern interpreters understand how certain groups, or even a large portion of the population, understood certain passages. In some cases, where the meaning of a passage is unclear, the Targum translation can bring clarity to what the passage intends to say.

and he shall uplift the omera before the Lord to be accepted for you: after the day of the festivity shall the priest uplift it. – Leviticus 23:11 (From the Targum Onkelos, c.35–120 CE.)8

and he shall uplift the sheaf before the Lord to be accepted for you. After the first festal day of Pascha (or, the day after the feast-day of Pascha) – Leviticus 23:11 (from the Targum Jonathan Ben Uzziel/Palestinian)9

The interpreters who wrote these early commentaries made it crystal clear to the 1st Century Jewish audience that the prevailing understanding of this passage was that the waving of the barley sheaf was on the day after the first day of Unleavened Bread.

History tells us that in the 1st Century at the Temple in Jerusalem, the Pharisaic Method of reckoning the barley sheaf was kept. Below are accounts from two 1st Century Jewish historians who testify that the Pharisaic Method was, in fact, how the barley sheaf was reckoned in Israel during the time of Yeshua.

There is also a festival on the day of the paschal feast, which succeeds the first day, and this is named the sheaf, from what takes place on it; for the sheaf is brought to the altar as a first fruit both of the country which the nation has received for its own, and also of the whole land. — Philo of Alexandria (20 BCE—50 CE)10

But on the second day of unleavened bread, which is the sixteenth day of the month, they first partake of the fruits of the earth, for before that day they do not touch them. — Flavius Josephus (37 CE—100 CE)11

Both of these accounts record that in the 1st Century, the barley sheaf was reckoned at the Temple in Jerusalem using the Pharisaic Method—that is: the day after the first day of Unleavened Bread, on Nisan 16th.

Another biblical witness can be found in the chronology of the crucifixion of Yeshua.

If Yeshua had Passover with his disciples on Thursday, this would put His crucifixion and burial on Friday, the first day of Unleavened Bread; which makes the weekly sabbath Nisan 16th and the day the first sheaf was to be waved in the Temple. John designates this particular sabbath as a “high day.”

Then the Jews, because it was the day of preparation, so that the bodies would not remain on the cross on the Sabbath (for that Sabbath was a high day), asked Pilate that their legs might be broken, and that they might be taken away. – John 19:31

Tim Hegg makes this connection:

By calling the Sabbath a ‘great Sabbath,’ John is referring to the day when, according to the Pharisaic reckoning, the Sheaf was cut and waved and the count of days and weeks to Shavuot began. What could have made this day stand out even more in John’s mind is the fact that the controversy between at least one sect of the Sadducees (the Boethusians) and the Pharisees over when the Sheaf was to be waved would have meant that the ceremony was made as public as possible.12

The conclusion that Yeshua followed the Pharisaic Calendar can also be reached by mere observation of the Gospel narratives as Tim Hegg explains:

Whenever the Gospels portray Yeshua and His disciples attending a festival in Jerusalem, they do so when multitudes of other people are likewise celebrating the festival there. This is conclusive evidence that Yeshua followed the majority calendar, for He attends the festivals at the same time as did the majority of the Jewish population.13

The Pharisees were the majority of the Jewish population of the 1st Century. Throughout the Gospels we see Yeshua mostly interacting with the Pharisees. The Apostle Paul was a Pharisee and he continued to identify himself as such even after his conversion. The Sadducees are understood to be a minority group in Israel and their theology did not align with that of Yeshua, for they did not believe in the resurrection.

If the Pharisees were the majority of the Jewish population, it stands to reason that the Pharisaic Calendar would have been the calendar that Yeshua and His disciples followed.

Today we know that, in our fixed calendar, the Feast of Weeks will alway fall on Sivan 6th. However, in ancient times, the calendar was not fixed. The first day of each month was determined by observing the start of the new moon cycle. Once the new moon was seen and then proclaimed the new month began (Num 10:10, 28:11). Each Spring, once the first day of the first month was determined, the dates for Passover and Unleavened Bread were established and the date on which the first barley sheaf was to be waved was assigned; and 50 days later would be the Feast of Weeks. The days had to be counted because The Feast of Weeks is the only appointed time in the Spring that does not fall within the month of Nisan. But the purpose for counting the days from Passover to the Feast of Weeks is to connect the Exodus from Egypt and the giving of the Torah on Mount Sinai.14

Furthermore, the Lord has established times for us to worship Him. There are specific times of the day that sacrifices were to be made in the Temple. He commanded that silver trumpets are blown at the beginning of each month. He established the appointed times, festival days that are to be kept annually on specific dates. And He has given us the Sabbath day, the only appointed time that is given a specific day of the week and not a specific date.

Because Messiah’s resurrection occurred on a Sunday, the first day of the week, the Christian Church has elevated this day of the week above all of God’s appointed times. Eventually, Sunday has come to replace the biblical, seventh-day Sabbath. This innovation was established by man and not commanded by Scripture. Only one day of the week has been elevated above the rest and set apart by God since creation. That is the Sabbath.

While a plain reading of Leviticus 23 may support the Sadducean Method of reckoning when to celebrate the Feast of Weeks, there is more scriptural and historical support for the Pharisaic Method.