Articles

Every verse of each section of Psalm 119 has some reference to the Torah. The rich array of vocabulary used as synonyms for “Torah” includes ‘eidut, “decree,” piqud, “precept,” chuqah, “statute,” mitzvah, “commandment,” dereq, “way or path,” davar, “word,” mishpat, “ordinance,” and others.

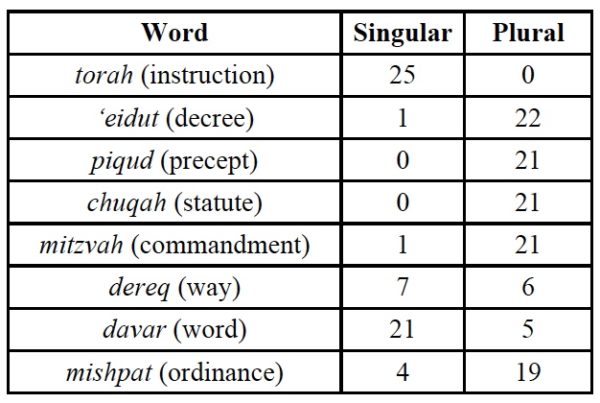

One of the interesting things that occurs in this great Torah Psalm (and indeed, throughout the Scriptures) is the fact that often the words chosen to denote the Torah are found both in the singular and the plural. Utilizing just Psalm 119, the following table will illustrate this phenomenon, showing how many times each of these various terms are found in the singular and plural in this Psalm:

Some of you might wonder why I would even think the word torah would be found in the plural. It might surprise you to know that torah is found in the plural 15 times in the Tanach: Gen 26:5; Ex 16:28; 18:16, 20; Lev 26:46; Is 24:5; Jer 32:23; Ezek 43:11; 44:5, 24; Psa 105:45; Dan 9:10; Neh 9:13.

But why am I interested in the singular and plural forms of these terms, you might ask? My interest lies in the fact that often (as the table notes above), the singular form stands for the whole. Or to put it simply, when the Psalmist declares “Your word stands firm in heaven,” he uses the singular form of davar, “word,” to represent all of God’s instructions—the whole Torah. This use of the singular really caught my attention when I continued to see the way the word mitzvah, “commandment” is found in the singular. Consider the following:

Now the LORD said to Moses, “Come up to Me on the mountain and remain there, and I will give you the stone tablets with the Torah and the commandment which I have written for their instruction.” (Ex 24:12)

Now this is the commandment, the statutes and the judgments which the LORD your God has commanded me to teach you, that you might do them in the land where you are going over to possess it, (Deut 6:1)

It will be righteousness for us if we are careful to observe all this commandment before the LORD our God, just as He commanded us. (Deut 6:25)

Therefore, you shall keep the commandment and the statutes and the judgments which I am commanding you today, to do them. (Deut 7:11)

For if you are careful to keep all this commandment which I am commanding you to do, to love the LORD your God, to walk in all His ways and hold fast to Him, (Deut 11:22)

if only you listen obediently to the voice of the LORD your God, to observe carefully all this commandment which I am commanding you today. (Deut 15:5)

For this commandment which I command you today is not too difficult for you, nor is it out of reach. It is not in heaven, that you should say, ‘Who will go up to heaven for us to get it for us and make us hear it, that we may observe it?’ Nor is it beyond the sea, that you should say, ‘Who will cross the sea for us to get it for us and make us hear it, that we may observe it?’ But the word is very near you, in your mouth and in your heart, that you may observe it. (Deut 30:11–14)

Only be very careful to observe the commandment and the Torah which Moses the servant of the LORD commanded you, to love the LORD your God and walk in all His ways and keep His commandments and hold fast to Him and serve Him with all your heart and with all your soul. (Josh 22:5)

The statutes and the ordinances and the Torah and the commandment which He wrote for you, you shall observe to do forever; and you shall not fear other gods. (2Kings 17:37)

The precepts of the LORD are right, rejoicing the heart; The commandment of the LORD is pure, enlightening the eyes. (Ps 19:8)

This use of the singular term “commandment” is also found in the Apostolic Scriptures:

And He answered and said to them, “Why do you yourselves transgress the commandment of God for the sake of your tradition? (Matt 15:3)

Neglecting the commandment of God, you hold to the tradition of men. He was also saying to them, “You are experts at setting aside the commandment of God in order to keep your tradition. (Mark 7:8–9)

But sin, taking opportunity through the commandment, produced in me coveting of every kind; for apart from the Torah sin is dead. I was once alive apart from the Torah; but when the commandment came, sin became alive and I died; and this commandment, which was to result in life, proved to result in death for me; for sin, taking an opportunity through the commandment, deceived me and through it killed me. So then, the Torah is holy, and the commandment is holy and righteous and good. Therefore did that which is good become a cause of death for me? May it never be! Rather it was sin, in order that it might be shown to be sin by effecting my death through that which is good, so that through the commandment sin would become utterly sinful. (Rom 7:8–13)

I charge you in the presence of God, who gives life to all things, and of Messiah Yeshua, who testified the good confession before Pontius Pilate, that you keep the commandment without stain or reproach until the appearing of our Lord Yeshua Messiah, (1Tim 6:13–14)

What is significant about this use of the word “commandment” (מִצְוָה, mitzvah; ἐντολή, entole) in the singular? Its importance is this: it highlights an obvious fact, found throughout the Scriptures, that the Torah is viewed as an indivisible unit—one whole piece of cloth that cannot be divided. This foundational truth is emphasized all the more when the singular “commandment” is found in the context of other plural terms used to describe God’s Torah. In this regard, note Deut 7:11 as an example. Here, Moses exhorts Israel to “keep the commandment” (singular) which is obviously equivalent to the following “statutes” and “judgments” (plural). The authors of the Scriptures refer to the whole of Torah by the singular “commandment” or “word” because they naturally view the instructions given to us by God as a unified whole. Surely the Torah contains many mitzvot (plural), but they are not considered by Moses, the Prophets, or the Apostles as segmented but as a unified body of truth and instructions for God’s people.

Yeshua makes this clear in Matt 5:17 when He begins by referencing “the Torah and the Prophets.” Yet it is clear in the following verses that His primary focus is upon the Torah and commandments of God. Yeshua is teaching us that all of God’s revelation is Torah, and that any attempt at dividing it up into sections, making some parts important and others of less importance, or even irrelevant, is dead wrong. Even the smallest stroke of God’s revelation remains eternally established in heaven. When the Christian theologians sought to divide the Torah into Moral, Civil, and Ceremonial categories, they conveniently overlooked the fact that the word of God is a unified whole that cannot be divided. The reality is this: if any part of God’s word may be set aside as irrelevant, it all may be set aside.

This is what arrested my attention as I recently contemplated Ps 119 once again. When, in v. 89,1 the Psalmist (by the Spirit, cf. Matt 22:43) declares: “Your word stands firm in heaven,” he uses the singular דָּבָר, davar, “word.” We therefore are warranted in understanding these words to mean: Your word, all of it, stands firm in heaven.” If man, in his own pseudo-theology, declares that some of God’s revelation is no longer authoritative; if he seeks to “unshackle” modern man from the “antiquated” rules of “ancient Israel;” or if he proclaims that “Jesus has abolished the old way by bringing in a new one;” he flies in the face of the Almighty and stands against what Heaven has declared: “The grass withers, the flower fades, but the word (singular) of our God stands forever” (Is 40:8).

Most evangelical Christians would heartily agree that God’s word is eternal, all the while treating many of the very words of God as irrelevant and without current authority for them personally. But it may shock you to know that there are many people in the Torah movement who are not much different in their perspective. While they teach the eternal viability and authority of the Torah, they subtly undermine this foundational truth by suggesting that parts of the Torah are only for the physical descendants of Jacob.

Most often, their argument goes this way: since we know that there are some laws given specifically to women and not to men (and vice versa), some given only to kings while others are restricted to priests, etc., it proves that not all of the commandments are for everyone. Having established this principle, they go on to affirm that there are therefore some laws given only to the Jewish and not to the non- Jewish people. This argument is a non sequitur for the simple reason that when the commandments are given to a specific group, the Torah itself makes this amply clear. So if the Torah similarly announced that “this law” or “that statute” is for the Jewish person or native born only, then the argument would be consistent. But where does the Torah speak in such specificity? Someone might respond with Lev 23:42, “You shall live in booths for seven days; all the native-born in Israel shall live in booths.” But note the parallel commandment in Deut 16:11 which clearly applies the command to dwell in sukkot during the festival to “your male and female servants and the Levite who is in your town, and the stranger and the orphan and the widow who are in your midst.” It is interesting to note that in almost every instance where the word “native born” (אֶזְרַח ’ezrach) is found in the Torah, “stranger, foreigner” (גֵּר, ger) is found in close proximity.2 If the principle, that God gives specific commands to specific groups, is used to support the idea that God gave specific commands to Jewish people which do not apply to non-Jewish people, then to be consistent, the Torah should detail specifically what these commands are. The fact that the Torah does not do this makes the argument a non sequitur. Those who hold such a position, that certain commands apply only to Jewish people, assert their own judgment as to just exactly what commands these are. Their determinations are based on their own ideas, or upon the rulings of the Sages, but not upon Scripture.

Even more subtle is the argument that only the Jewish people have a direct relationship to the Torah and that believing Gentiles, who “join themselves to Adonai” (cf. Is 56:3), have only a secondary relationship. Such a theological position leads to the conclusion that Jewish people are obligated to obey the Torah (since they have a primary relationship to the Torah as covenant members) while believing Gentiles are given a divine invitation to obey it, an invitation which (presumably) they can accept or reject. Here, again, the Torah is viewed as segmented, for even those who hold such a position would be quick to affirm that believing Gentiles are obligated to keep the “moral” commandments.

The reason that I put the word “moral” in quotes in the above sentence is because it is impossible to make a clear distinction between the commandments, as though some are “moral” and others are not. Take the commandment of the Shabbat, for instance. Does this commandment fall into the category of “moral” laws? Surely it must, for the Torah speaks of “profaning” the Shabbat (Ex 31:14; Is 56:2) and refers to the day as “holy” (Ex 16:23; 20:11; 31:14–15). Moreover, breaking the Shabbat is a capital offense (Ex 31:14–15). In Isaiah 56:2, the one “who keeps from profaning the Shabbat” is further described as one who “keeps his hands from doing evil (רַע, ra‘).” All of these terms make it clear that the Sabbath commandment pertains to that which is ethical or moral. Indeed, God Himself is the standard of what is moral or immoral, ethical or unethical, right or wrong, and He has revealed His holy standard to us in the Torah—all of it.

Thus, when Paul states that “the Torah is holy, and the commandment is holy and righteous and good” (Rom 7:12), he uses the singular “commandment” to emphasize the unity of the Torah, meaning that all of it pertains to what is “holy, righteous and good,” not just some of it. And in v. 14, he writes that the Torah is “spiritual,” meaning that it pertains to what the Spirit is urging God’s people to obey. To argue that Paul had only some of the commandments in mind when he wrote this to the predominantly non-Jewish Roman community of believers is preposterous.

Some might argue that even Yeshua spoke of the “weightier matters of the Torah” (Matt 23:23), from which they derive the idea that some of the Torah must then be “lighter matters” and therefore of lesser importance. Such eisegesis is easily corrected by simply reading the words of our Master in this very context. He emphasizes that both the weightier and the (apparent) lighter matters are to be guarded and kept: “…these are the things you should have done without neglecting the others.” Indeed, His words that “…not the smallest letter or stroke shall pass from the Torah until all is accomplished” (Matt 5:18) make it amply clear that He considered all of the Torah, down to the last inspired letter, of utmost importance.

But what about the idea that the Jewish people, those who throughout earth’s history have traced their physical lineage to Jacob, have a relationship to the Torah that non-Jewish people do not have? At first this may seem to solve a number of thorny problems, chief among which is the ugly doctrine of supersessionism or replacement theology. Surely God has promised His faithfulness to the physical offspring of Jacob. And no one can deny the obvious fact that God gave the Torah to Israel and in so doing made a covenant with the nation of Israel and not with any other nation, a covenant that He promises to maintain even when Israel is disobedient. But then what about non-Jewish people who, through faith in Israel’s God and His Messiah, Yeshua, join Israel by being grafted into the covenant “Olive Tree” (Paul’s metaphor in Rom 11)? Do such non-Jewish people become members of the same covenant given initially to Israel? When the child of a non-Jewish believer asks regarding the celebration of Pesach, “What is this?”, can his parent respond by saying “With a powerful hand the LORD brought us out of Egypt, from the house of slavery” (Ex 13:14)? Can the non-Jewish believer join in the Amidah and praise the “God of our fathers, God of Abraham, God of Isaac, and God of Jacob?” Paul unhesitatingly answers in the affirmative, for he boldly states that all of us, Jew and non-Jew alike, have Abraham as our father (Rom 4:16, cp. Gal 3:29). If some Jewish believers feel that such a position hedges towards replacement theology, then they need to understand that believing Gentile brothers and sisters are not replacing but expanding Israel, just as the prophets foretold (Zech 2:11). God has one family, not two; He has one bride, not two. He is not a polygamist. Indeed, God has given us a glimpse of how the whole story ends (Rev 21), and we see that there is one bride, represented by the holy city, the new Jerusalem, that comes down out of heaven and is adorned and ready for her groom. The prophetic picture is not of Athens and Jerusalem—it is Jerusalem alone, the place where God put His Name, His heart, His ears, and His eyes forever—the very city that in the Prophets stands for the whole nation of Israel (e.g., Is 4:4; 30:19; Zech 2:12; 3:2; cp. Heb 12:22).

But why does the new Jerusalem come down out of heaven in John’s apocalyptic metaphor? It is because all who are citizens of this city are so because of God’s sovereign choosing. It is God Who chooses the bride for His Son, not vice versa, and this bride is the host of people that no one can number, of every tribe, kindred, and tongue, who have been gathered together as God’s people, standing forever as trophies of God’s grace, of what He can make out of nothing. The idea, then, that there are “primary” covenant members and “secondary” is in direct conflict with the Scriptures.

There is one more point I wish to emphasize, namely, that God’s love is the same for each member of His family. Now this fact also bears upon the question of whether a Jewish person has a different relationship to the Torah than does a non-Jewish person within God’s family. This is because, among the manifold ways in which God’s love is made known to us, one is by means of discipline: “For those whom the Lord loves, He disciplines, even as a father corrects the son in whom he delights” (Prov 3:11– 12, cf. Heb 12:5–6). Parental discipline or correction comes when a child has erred or disobeyed. A mom or dad disciplines in love because they want the best for their children. Now let us apply this to the idea that obedience to the Torah is simply a divine invitation and not an obligation for non-Jewish believers. In such a scenario, there is no basis for God to discipline since there is no real transgression: politely saying “no” to the invitation to Torah removes that person from the obligation to obey it. But it also removes that person from being disciplined. Obligation and the discipline that attends it is the mark of being one of God’s children.

I can give an illustration from my own family. As most of you know, my wife and I have two naturally born sons, and two adopted daughters. It is readily apparent to all who see us that our daughters have a different ethnicity—they are from Liberia, West Africa. Consider this scenario: years ago, when we were abundantly privileged to have our daughters join our family, we are sitting down at the dinner table to establish our “house rules.” I look at my two sons and remind them that they are to be in bed no later than 10:00pm, and I also reinforce the fact that if they fail to obey this rule, they will be disciplined. Then I turn to my daughters, and I say, “You are both welcomed to also observe the 10:00pm rule of being in bed. In fact, it would please me if you would.” That evening, I stop by my son’s bedrooms to make sure they have complied, and sure enough, lights are out and they’re in bed. But when I come to my daughter’s rooms, they are both still active and show no sign of even getting ready for bed. What is my response? Can I approach them by saying “Why didn’t you obey me?” No, I cannot, for the simple reason that an invitation does not bring obligation. By its very nature, an invitation leaves the outcome in the hands of the one invited. And in fact, this very principle is well known: children come to understand the genuine love of a parent, not when the parents suspend all boundaries, but when boundaries are established and lovingly enforced. And this is true in God’s family as well. All of His children have the same “house rules” and thus all of them experience His love when He disciplines them in order to bring them back into conformity to what He has commanded. Those who are not disciplined, who sense no personal obligation to obey His commandments, are those who are outside of His family.

The primary points that I hope to have emphasized in this short essay are these: 1) the Torah is eternal and is a unified whole which cannot be divided, 2) God has given the Torah by way of covenant to Israel, 3) all those from the nations, non-Jews, who attach themselves to the God of Israel by faith in His Messiah, Yeshua, are joined to Israel and therefore become covenant members with equal obligations and privileges, and 4) that such obligation to obey God’s Torah is the very mark of being His children, proven by the fact that He disciplines those within, not those outside, His family.

Tim Hegg

President / Instructor

Tim graduated from Cedarville University in 1973 with a Bachelor’s Degree in Music and Bible, with a minor in Philosophy. He entered Northwest Baptist Seminary (Tacoma, WA) in 1973, completing his M.Div. (summa cum laude) in 1976. He completed his Th.M. (summa cum laude) in 1978, also from NWBS. His Master’s Thesis was titled: “The Abrahamic Covenant and the Covenant of Grant in the Ancient Near East”. Tim taught Biblical Hebrew and Hebrew Exegesis for three years as an adjunct faculty member at Corban University School of Ministry when the school was located in Tacoma. Corban University School of Ministry is now in Salem, OR. Tim is a member of the Evangelical Theological Society and the Society of Biblical Literature, and has contributed papers at the annual meetings of both societies. Since 1990, Tim has served as one of the Overseers at Beit Hallel in Tacoma, WA. He and his wife, Paulette, have four children, nine grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren.