Articles

6:14 For sin shall not be master over you, for you are not under Torah, but under grace.

The fact that sin no longer is master (κυριεύσει, kureusei “act as lord or master”) is because the old man has been crucified and no longer has the power to direct sin within the sinful nature to deeds of unrighteousness. Left without “leadership,” and with the renewed man now “in charge” and longing to follow the Lord and live righteously, the remaining sin is at a distinct disadvantage, for the inevitable course of the believer’s life will be toward God and away from sin.

Does Paul, by the opening statement, make a statement of fact, or is he making an exhortation to his readers? We may sum up the interpretations as follows:

1) Paul makes a promise to his readers that never again will they yield to sin. This is surely not possible, for Paul goes on to show that believers, while not under the reign of sin, still sin nonetheless.

2) Paul exhorts his readers not to allow sin to usurp mastery over them. This appears attractive at first, but such an interpretation would render the verse a mere reiteration of v. 12, and would therefore seem somewhat superfluous. What is more, the opening of the verse with “For” (gavr, gar) as an explanation of what has been stated previously does not seem to work.

3) Paul makes a categorical statement that sin, personified as a ruler, will never again have sovereign rule over them because a new Lord has taken His rightful place over their lives. This explanation understands the opening “for” to explain why the believer should not present his members as instruments of unrighteousness—namely, because he now serves a new Master. There is no need, as it were, to appease the master of unrighteousness, for he no longer has any ruling power.

This does not mean that sin will no longer have power, for it will—in the remaining sinful nature. Thus, it also means that sin will be a constant enemy against which war will be waged. What it does mean, however, is that hope of victory is sure, because the war has already been won—the enemy’s “general” has been deposed.

For you are not under Torah but under grace – Taken out of context, this phrase has regularly been interpreted by Christian commentators to mean that the authority of the Torah has been abolished for believers and superseded by a different authority, that by “law” (νόμος, nomos) Paul means the life of sin, and by “grace” he means the life of righteousness. Note for example, the words of Ambrosiaster (366 CE):

If we walk according to the commandments which he gives, Paul says that sin will not rule over us, for it rules over those who sin. For if we do not walk as he commands we are under the law. But if we do not sin we are not under the law but under grace. If, however, we sin, we fall back under the law, and sin starts to rule over us once more, for every sinner is a slave to sin. It is necessary for a person to be under the law as long as he does not receive forgiveness, for by the law’s authority sin makes the sinner guilty. Thus the person to whom forgiveness is given and who keeps it by not sinning anymore will neither be ruled by sin nor be under the law. For the authority of the law no longer applies to him; he has been delivered from sin. Those whom the law holds guilty have been turned over to it by sin. Therefore the person who has departed from sin cannot be under the law.1

Rather, the context shows clearly that Paul’s point in this concluding phrase is that the reign of sin had its power or authority through the Torah, for the Torah condemns sin and the sinner. Paul has taught clearly that the power of sin to condemn is found in the Torah. Thus, when he concludes that the believer is not under the Torah but under grace, he is not putting the Torah and grace at odds with each other, but showing the means by which the believer is no longer a slave to sin but instead is alive unto God. The penalty of the Torah against the sinner, just and righteous as it was, was put entirely upon Yeshua and therefore the believer is no longer under its condemnation. In the place of condemnation has come forgiveness and grace.

Cranfield has this to say:

[this phrase] is widely taken to mean that the authority of the law has been abolished for believers and superseded by a different authority. And this, it must be admitted, would be a plausible interpretation, if this sentence stood by itself. But, since it stands in a document which contains such things as 3:31; 7;12, 14a; 8:4; 13:8-10, and in which the law is referred to more than once as God’s law (7:22, 25; 8:7) and is appealed to again and again as authoritative, such a reading of it is extremely unlikely. The fact that ὑπο νόμον (“under law”) is contrasted with ὑπὸ χάριν (“under grace”) suggests the likelihood that Paul is here thinking not of the law generally but of the law as condemning sinners; for, since grace denotes God’s undeserved favour, the natural opposite to “under grace” is “under God’s disfavour or condemnation.” And the suggestion that the meaning of this sentence is that believers are not under God’s condemnation pronounced by the law but under His undeserved favour receives strong confirmation from 8:1 (“There is therefore now no condemnation to those who are in Christ Jesus”), which, in Paul’s argument, is closely related (through 7:1-6) to this half-verse. Moreover, this interpretation suits the context well; for an assurance that we have been set free from God’s condemnation and are now the objects of His gracious favour is indeed confirmation (γάρ, “for”) of the promise that henceforth sin shall no more be lord over us, for those who know themselves freed from condemnation are free to resist sin’s usurped power with new strength and boldness. It is perhaps possible that in Paul’s “under law” here there was also another thought present, namely, the thought of labouring (as so many of his Jewish contemporaries were doing) under the illusion with regard to the law that a man has to earn a status of righteousness before God by his obedience. Since χάρις (“grace”) denotes God’s free, undeserved favour, the contrast with “under law” might perhaps be not unreasonably claimed as support for this suggestion.2

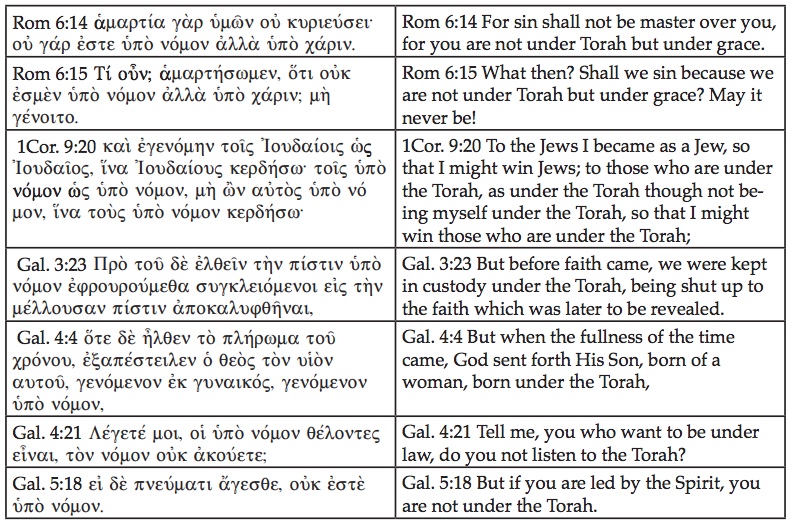

It may be profitable for us to consider all the times the phrase “under Torah” (ὑπο νόμον, hupo nomon) is used in Paul’s epistles as we attempt to understand what it means.

Passing by Rom 6:15 (which we will move to next), let us look individually at each of the other passages.

1Cor 9:20 – In the context Paul is arguing that as a servant of Yeshua he has every right to enjoy the fruit of his labors. Even as the farmer eats the crops he sows and harvests, and the threshing floor worker is free to eat of the grain he threshes, so Paul has a right to expect material help from those he feeds spiritually. The fact that his apostleship has come into question in the minds of some does not negate the valid ministry he has accomplished among the Corinthians. Yet just because he has been willing to minister without remuneration and support, some are saying he is less than a valid apostle. He thus explains that his decision to serve the Corinthians without remuneration was a conscious decision on his part and one he was free to make. In fact, his decision to work for his own living and not take the support of the Corinthian church was done in order to advance them in their spiritual growth. He felt, for one reason or another, that had he taken support from them, his ministry to them would have diminished.

In vv. 19–22, Paul presents his teaching in a literary structure that utilizes pairs. In each pair, the first phrase is further explained by the second, parallel phrase.3

(A)I made myself a slave to all in order that I might gain more (v. 19)

(B)I became to the Jews as a Jew, in order that I might gain Jews (v. 20a)

(B1) To those under the Torah as under the Torah…to gain those under the Torah (v. 20b)

(C)To those outside of Torah as outside of Torah…to gain those outside of Torah (v. 21)

(C1) To the weak I became weak in order that I might gain the weak (v. 22a)

(A1) I have become all things to all in order that I might save some of them (v. 22b)

Note that the opening and concluding phrases (A, A1, each containing the term “all”) form a pair that function as “book ends” for the section. These “book ends” frame two sets, each with two lines, describing two different groups of people. The first group (B, B1) is defined as “Jews,” further defined as “those under the Torah.” Here Paul is describing the traditional, non-Yeshua synagogue community, who proudly claimed submission to the Torah as the primary marker of their Jewish status. The second group (C, C1) is defined as “outside of Torah” and “weak,” labels used by the non–Yeshua synagogue community to describe the followers of Yeshua, especially those synagogues of The Way that were marked by a majority of Gentile believers. They were considered “outside of Torah” because they did not have “legal Jewish status,” and they were therefore “weak,” meaning they had no ability to stand righteous before God (cp. Rom 5:6, where the same Greek word, ἀσθενής, asthenes, “weak” is used). The prevailing rabbinic theology of the 1st Century was that only those with a legal Jewish status (native born or proselytes) could be received by God as righteous.4

Paul is therefore contrasting two groups: the non–Yeshua believing synagogue community and the Yeshua-believing synagogues of The Way. Given this understanding, the designation “under the Torah” offers Paul a double entendre. While the non–Yeshua synagogue community consider “under the Torah” to be a primary mark of its Jewish (and therefore “righteous”) identity, Paul recognized that basing one’s righteousness on one’s legal Jewish status as maintained by Torah observance was actually to place oneself under the condemnation of the Torah.

Paul states that he put himself “as under the Torah,” though he quickly emphasizes that he was not actually “under the Torah” (i.e., under the condemnation of the Torah). What then did he mean? He meant that he submitted to the synagogue authorities (he took lashes five times, cf. 2Cor 11:24) in order that he might maintain his membership within that community, so that he might continue to have opportunity to proclaim the gospel there. Thus, “under the Torah” here has the same meaning as elsewhere in Paul, i.e., “under the condemnation of the Torah.”5

Gal 3:23 – We may begin first of all by discussing what Paul means in this verse by the term “faith”—“But before faith came . . . .” Now certainly Paul cannot mean here that there was no faith before the coming of Yeshua! Paul is the expounder of Gen 15:6 in Romans 4 and uses Abraham and David as the examples of what it “looks like” to have faith—saving faith. So what does Paul mean by the phrase “but before faith came . . . .?

Many commentators take the word “faith” here to be a metonym for Yeshua, i.e., the object of faith. So they would understand it to mean “But before Yeshua came we were kept in custody under the law, being shut up to the faith (in Yeshua) which was later to be revealed.” But this interpretation does not work either, for the simple and obvious reason that faith, i.e., true saving faith, has always been in one object and one object alone, namely, Yeshua. Faith in the Messiah has always been the means by which God declares a sinner righteous. Surely this is proven in the case of Abraham, for Yeshua Himself declared that Abraham longed to see His day, and he saw it (Jn 8:56f). David as well understood that the promise of the Messiah was the focus of his faith, as he likewise understood the Messiah to be the hope for all mankind (2 Sa 7:19f). Therefore, to say that “faith” in this verse actually means the object of faith, i.e., Yeshua, simply cannot be sustained in the broader scope of Pauline theology (not to mention the emphasis upon faith in the Messiah throughout the scriptures).

It seems to me that the plain meaning of the text ought to be our starting point. For Paul, the concept of something “coming” is that of “understanding” or “knowing the truth.” He uses this same idiom with regard to the Torah in Rom 7:9 where he writes: “And I was once alive apart from the Torah; but when the commandment came, sin became alive, and I died.” The commandment was always extant, and even was very much a part of Paul’s life before he came to faith in Yeshua, yet in his terminology it had not yet come. It “came” when by faith his eyes were opened to see the commandment as it actually was. That is to say, the concept of the commandment “coming” is that of knowing the truth about the commandment.

If we take Paul to be using the same concept here, in regards to faith, then the phrase “before faith came” means before Paul (or any given individual) came to understand faith as it truly is—faith as God understands it. Thus, as a Jew, living within the context of Torah observance yet without faith in the Messiah, the Torah functioned to point to the Messiah in every way—through the sacrificial system, the mo’edim (festivals), purity laws, etc. The Torah continued to function as a pedegogue leading to the teacher, restraining (in some ways) the natural tendencies of the flesh and directing the mind and heart to faith in Yeshua. Once Paul had genuinely placed faith in Yeshua, the Torah no longer needed to function in this convicting manner (as a pedegoguefor an immature child) but took up the role of mentor, deepening the understanding and enlightening the willing mind.

Thus, to be “kept in custody under the Torah” is to be surrounded with the observance of Torah (as was generally true of the Jewish community of Paul’s day) in contradistinction from the pagan cultures whose lives were surrounded by idolatry, etc. Paul wishes to show, then, that the Torah, while condemning the sinner, nonetheless functions to lead the sinner to Messiah, if in fact that sinner is being drawn by the Almighty—drawn to faith in Yeshua.

Here, then, we may understand “under Torah” to mean “compelled by the Torah to do those things which, though contrary to an unbelieving heart, actually point toward Yeshua.” To put it another way, to be “under the Torah” in this context is analogous to being under the rule of a pedegogue whose primary goal is to get the student to graduation.

Gal 4:4-5 – It is easy to see why many commentators have understood Paul’s use of “under the Torah” in these verses to simply mean “born as a Jew to redeem Jews.” That Yeshua was born to Jewish parents, and that the first events in His life were circumcision and appearance at the Temple is emphasized by the Gospel writers (cf. Lk 2:21ff). But the parallel with 3:13-14 is so close as to warrant a continuing theme, namely, that one of the roles of the Torah as it pertains to the unbeliever is that of condemnation (cf. 2Cor 3:7ff). The Torah condemns sin and thus the sinner.

But was Yeshua born “under the condemnation of the Torah?” In one sense, He was not. As the perfect and holy Son of God, He did not partake of Adam’s sin, and as such, was not born a sinner (cf. Rom 5:12f). But in another sense, He was born for the purpose of carrying the condemnation of His people, and in this sense He was born “under the condemnation of the Torah” as it pertains to their sins.

For Paul, the ministry of Yeshua was conceived of as primarily soteriological. His coming was not primarily as a teacher of Torah or of wisdom as much as it was to identify with the human condition (“born of a woman”) “in order that, by His identification with the human condition . . . , His death might be the price necessary to free them from the slavery endemic to that human condition…”.6 In this regard then, we should most likely see Paul’s use of “born under the Torah, so that He might redeem those under the Torah” to be a reference to Jew and Gentile alike. Even though the Gentile has no sense that he is condemned by the Torah until such time as he hears the message of the Gospel, he is nonetheless in a state of condemnation. He is “under the Torah” in the sense of being under its condemning power. Likewise, the Jew, who may have never considered that the Torah would condemn him, is under the condemnation of the Torah until such time as he places his faith in the redemptive work of Yeshua. We may conclude that “under the Torah” in this context means “under the condemnation of the Torah.”

Gal 4:21 – In this verse Paul speaks of those who “want to be under the Torah,” and asks them to listen to the Torah they want to be under. In an interesting (and somewhat difficult to interpret) analogy, Paul compares the present state of Judaisms to Hagar as a slave while speaking of the “Jerusalem above” as free and analogous to Sarah (though she’s actually never named). Clearly the “slave” is the one who believes his covenant membership rests upon his status as a Jew (whether native born or proselyte). In such a case, those who are relying upon the “flesh” (ethnic status) for their right standing before God are actually under the condemnation of the Torah. While on the one hand they believe that the Torah, as marking their identity as Jews, is their means of covenant membership, in actuality the Torah is the forensic means of their condemnation. Once again, “under the Torah” means “under the condemnation of the Torah.”

Gal 5:18 – Here Paul is contrasting the leading of the Spirit with being “under the Torah.” Note v. 16ff: “But I say, walk by the Spirit, and you will not carry out the desire of the flesh; for these are in opposition to one another, so that you may not do the things that you please. But if you are led by the Spirit, you are not under the Torah.” Once again, to be under Torah means to rely upon the Torah (both written and oral) as the means of establishing covenant membership through ethnic status. For the native born, this meant maintaining Torah obedience in order not to be “cut off from one’s people,” while for the Gentile it meant undergoing the ritual of rabbinic conversion (becoming a proselyte). In both cases, those who are “under the Torah” are condemned by the Torah because they are trusting in “the flesh” (ethnic status) as defined by the rabbinic interpretation of Torah.

In summary, then, “under the Law (Torah)” means primarily “under the condemnation of the Torah,” or may define those who are relying upon the Torah to give them a “Jewish status” which they believe is the means of covenant membership. Thus, in our text, being “under the condemnation of the Torah” is contrasted with “being under grace.” Those who are “under the Torah” are those who (whether Jews or Gentiles turned proselyte) are relying upon their Jewish status (i.e., “the works of the Torah”) for covenant membership, and as such, remain under the condemnation of the Torah. In contrast, those who are “under grace” have relied entirely upon God’s gift of salvation as a matter of His pure and sovereign grace. Their striving to maintain (or obtain) their covenant status through the “works of the Torah” has ceased, and they have accepted the rule of grace in their lives—a rule administered by the presence of the indwelling Spirit.

15 What then? Shall we sin because we are not under Torah but under grace? May it never be!

Having looked briefly at the Pauline passages where the phrase “under Torah” is found, we are now in a better position to interpret the verse before us.

It may at first appear that Paul is simply asking the same question he began the chapter with (6:1) in which he answers the false premise which some may have built upon 5:20. If where sin abounded, grace did much more abound, could it be inferred from this that one should sin all the more? The answer is an emphatic “God forbid” (may it never be). But the question which he now poses in our text is, in fact, not the same, for it poses a second false inference, namely, that if a person is no longer under the penalty of the Torah, then actions which before constituted sin are now amoral. To put it another way, if sin is only known in relationship to the Torah, and if the Torah is no longer active in its condemning function, then sin is without definition. But to this second false inference Paul answers with the emphatic μὴ γένοιτο, me genoito, “may it never be.” For far from not making any difference to the believer, sinful acts now take on even a greater concern for they are contrary to the renewed nature of the redeemed soul.

The pains to which Paul goes in the subsequent verses to prove the premise false may well highlight the fact that some actually believed this theological error and were practicing this blantant form of anti-nomianism.

Tim Hegg

President / Instructor

Tim graduated from Cedarville University in 1973 with a Bachelor’s Degree in Music and Bible, with a minor in Philosophy. He entered Northwest Baptist Seminary (Tacoma, WA) in 1973, completing his M.Div. (summa cum laude) in 1976. He completed his Th.M. (summa cum laude) in 1978, also from NWBS. His Master’s Thesis was titled: “The Abrahamic Covenant and the Covenant of Grant in the Ancient Near East”. Tim taught Biblical Hebrew and Hebrew Exegesis for three years as an adjunct faculty member at Corban University School of Ministry when the school was located in Tacoma. Corban University School of Ministry is now in Salem, OR. Tim is a member of the Evangelical Theological Society and the Society of Biblical Literature, and has contributed papers at the annual meetings of both societies. Since 1990, Tim has served as one of the Overseers at Beit Hallel in Tacoma, WA. He and his wife, Paulette, have four children, nine grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren.